Hi Folks,

It’s Sunday again. Somehow it is April, though I often still fail to see how we have ended up back here already. Lately it feels that days pass and repeat and become indistinguishable from each other. There are patterns, and there is loneliness. There is an underlying, gnawing sense that nothing is enough, that everything has fundamentally changed, that the world that was once keenly felt— a world of joy and connection and hope— is slipping further and further away and will never feel within reach again. The news reinforces this. The news tells every day of further tragedy, drawing a deep line between memory and reality, past and present.

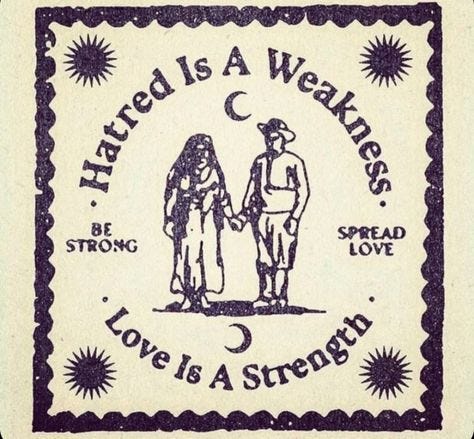

I have cried three times this week, which is more than I used to cry in a year. I write this because it feels cathartic to do so, and also important. I have said many times to those around me that the choice of happiness is one of the greatest forms of rebellion we possess, because there is so little in the world today that wants us to be happy, truly content, not desiring of more or thinking of a different life, but simply living within the one we already possess and feeling at peace with the choice to do so. It is not easy to do this. For a long time I sincerely believed that I would never be truly happy, and that this was just a symptom of modern life. For a long time I didn’t see a point in struggling for joy, in waking up each day and choosing it over and over again. What is the end point of joy? Is there one? Will I spend the rest of my life having to make the active decision to call it into my existence, to fight the urge to give in to despair, isolation, all the horrors that the world throws at us every time we turn on the television or open up a newspaper or even simply scroll through our phones? Is all of this worth it?

Someone once told me that I spend too much time asking these questions in my head and making myself miserable over them. That they didn’t think I would ever allow myself happiness because I would never be able to stop looking into the eye of tragedy. At the time I believed them. But now I wonder where we draw the line, because I think these are important questions to ask, and even if they aren’t, I know my brain will never stop asking them. I would like to know how to ask these questions and survive. How to approach the difficult thing with tenderness, and how to walk away from it that way, too.

In college I spoke often to my peers of empathy, and it was not always well-received. I distinctly remember a seminar where, sitting around a long wooden table, I listened to my peers debate the pointlessness of it. We will never truly be able to understand what another person feels, they said, so why even try at all? Their argument was that we should all return to ourselves and our own problems and stop trying to pretend we will be able to learn the struggles of another. In many ways, they are right. It is true that we will never be able to fully understand what others have gone through. It is true that the technical definition of empathy supports this argument, defining it as “the ability to understand or share the feelings of another.” This definition of empathy, at times, turns it into something exploitative or demeaning; just look at how many white woman took to posting on social media last year that they had read one book on race and suddenly possessed vast empathetic capacities, writing that they never could have dreamt what others had gone through or how difficult it must have been. There is the idea with empathy that one conversation— or one podcast or film or novel— can suddenly make you an expert on another’s suffering, that the act of listening allows you to share in their pain. That day, the other students in the room took note of this, and decided that perhaps there was no point in practicing empathy at all.

I would be remiss if I let this newsletter go any further without bringing in Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams, the text that first got me interested in empathy work. The Empathy Exams is the title of Jamison’s first essay collection and also the name of the opening essay— which was later published in The Believer— about her experience as a medical actor. Jamison writes candidly about her own suffering, and the ways in which she sought out empathy from those around her— sometimes in damaging ways. I reread the essay this morning while sitting outside at a small coffee shop in the town over from the one I currently live in. It was warm, and I watched a neon green lizard crawl upward across the brick, wondering why I felt so sad, still, after all this time. Why the world seems to grow heavier for all of us every day now, and the loneliness— even in a room full of people— feels collective, suffocating, and endless. I wanted to be the lizard on the wall, darting in and out of dark cracks, watching as the world went on around me. I found myself struck by this passage of Jamison’s:

“I used to believe that hurting would make you more alive to the hurting of others. I used to believe in feeling bad because somebody else did. Now I’m not so sure of either. I know that being in the hospital made me selfish. Getting surgeries made me think mainly about whether I’d have to get another one. When bad things happened to other people, I imagined them happening to me. I didn’t know if this was empathy or theft.”

How many ways have I practiced this? How many times have I modeled my own pain on the pain of others, believing it would make me more interesting, give me more depth, even— gasp— allow me to better practice empathy? I used to think that in order to understand hurt I had to be intimately familiar with it first. I thought that was part of the deal; empathy required taking up the suffering around me. How could I know the hurt of others if I myself had not hurt in that way first? It was a half-hearted attempt to lighten the imagined burdens of those I interviewed, spoke to, interacted with. I would do what I could to take their pain away and, in return, I would integrate it into my own. What I thought was compassion was often just theft.

I used to think that feeling was an essential part of empathy, and that I could not feel unless I understood. But I am beginning to believe empathy requires a new definition. That it is not about making the attempt to understand another’s suffering, but about making the choice to care about them whether you will ever understand or not— because the honest truth is that most of the time, we will not. The idea that experience can be reduced to a single story— that we can read or listen and suddenly know someone in the way that empathy asks of us— diminishes our individuality, our complexity. It pretends that we are all simple creatures, when of course we are not.

Empathy is a paradox, because it is at once both selfish and not. It requires that we become deeply attuned to our own inner lives, our own stories and needs. We cannot demonstrate true empathy for others if we don’t first practice it towards ourselves. I sit at this little metal table and think: I do not want to hurt anymore. But more than that: If I am going to hurt, I do not want to hurt alone.

That is what empathy gives us: the ability to hold one another as we experience, even if our experiences remain individual. There is the scenario in which we do come across others who have suffered in the same ways we have, and in those cases, community can be built; we can look at one another around the table in the room and say, you are not alone, because I have felt this too. There is comfort in that knowledge. But there needs to be comfort without it too, a way to practice empathy so that it is not commodification, or theft, or exploitation. Jamison provides a great argument for presenting empathy as a decision to care:

“Empathy isn’t just something that happens to us—a meteor shower of synapses firing across the brain—it’s also a choice we make: to pay attention, to extend ourselves. It’s made of exertion, that dowdier cousin of impulse. Sometimes we care for another because we know we should, or because it’s asked for, but this doesn’t make our caring hollow. The act of choosing simply means we’ve committed ourselves to a set of behaviors greater than the sum of our individual inclinations: I will listen to his sadness, even when I’m deep in my own… This confession of effort chafes against the notion that empathy should always arise unbidden, that genuine means the same thing as unwilled, that intentionality is the enemy of love. But I believe in intention and I believe in work.”

Sometimes I return to that classroom where I sat and felt that the work I had been doing on empathy— nearly three years of research and travel and conversations and learning and unlearning, all leading to a thesis on empathy and rural communities— was worthless and lacking in value. That I had understood the topic all wrong, and should have just given it up and sacrificed to my greater impulse to give into my own narrative and live entirely inside my own head. That day, I said nothing. I felt shame that I believed this thing to be so important, so capable of changing the world. I wish now that I could go back and ask instead what a world without empathy would look like, because as much as I fear the uselessness of my work, I fear a world where we decide that care is pointless even more.

Your prompt this week is to reimagine yourself as the lizard in the garden. Do you dart openly between cafe tables, or do you remain hidden? Are you afraid of people? What does the world around you look like? Does it feel bigger or smaller than you imagined it to when you were human?

As always, reach out to us on email with any thoughts, questions, or stories. Also, if you missed it, we’re doing Thursday Resource Roundups now. Exciting!

Until next week,

Spencer

This week’s song is I’m So Tired by Fugazi, who originated in Washington D.C. The lyrics to this song sound quite sad, but I actually find it to be an uplifting melody. It feels like one of those songs in a movie where the character goes home alone at night and realizes one million things. I once drove through the hills at sunset listening to this and tapping out pretend piano keys on the top of my steering wheel and thought of myself as that character. I tend to always imagine myself as the movie character having a big, life-changing moment. Maybe that makes me self-obsessed. Hence the empathy work. Anyway, I’m sitting in the sun listening to this and feeling quite hopeful about the future and what it holds, and I think we all deserve a movie-realization-moment this week, so here you go.

Empathy can be exhausting. It's a lot to keep up with, everyone else all the time. It can even induce a kind of selfless mania, where the center no longer holds. I do find it more completing if I begin from a place of curiosity and I am willing to let go of hard-and-fast rules, e.g., philosophy, doctrine. If I don't require that people conform, it is easier to meet them where they are. If I really believe my life, workplace, etc., are better with different people around me, and I take steps to make that so, I approach true empathy that much more.

I am, therefore, uncertain of the lizard metaphor for me. I find empathy a process of translation, attempting to understand someone's language in my own. That's not easier, but it takes more than an understanding of scale to operate. The starting point is understanding that the language someone uses is not the language I choose for them, nor is mine the language they might choose for me. Agency is important here, too.

Good thoughts for me. Thanks. I loved The Empathy Exams, also.

Ok, then, from another time, a sad song-turned-moment of meaning: https://open.spotify.com/track/7qbLE7ssJcnWD6EO7My847?si=a3b7ef03729e43cb

Tom