Hi all,

I write this to you from the grey gloom of a rainy North Carolina afternoon. After a winter of turning inward and a spring that has thus far felt intensely busy, today I found myself—finally—wanting to turn back to the page. There’s lots to say here about actual Good Folk related operations (a great live event with Fatwood and WXYC last week! a status update on the podcast and interviews! an accountability check about my own capacities to write and when you can expect to hear from me in your inbox!), but right now I don’t want to talk about any of that. So here is a different story instead.

A few weeks ago, I decided that it was finally time to purchase a handheld vacuum. We had taken our Christmas tree out to a local farm to burn it and my car was littered with pine needles and that, combined with the constant dust that comes from living in an old warehouse with no real insulation, had pushed me to the edge. Now, buying a vacuum seems like a stupid, meaningless thing; it should be easy, and one would assume the innovations of our contemporary society would make it easier than ever. I went to Target. They were sold out. I looked in Home Goods. They had none. I found myself, last grasp, turning to Amazon, where I was instantly bombarded with hundreds of different AI-generated photos of what appeared to more or less be the same vacuum, at varying prices, all made from varying AI-generated storefronts that promise customer satisfaction and functionality. I ordered one of these vacuums and a few days later, it arrived. It has no brand on it, no label. It plugs into a random cord for charging that I hope I do not lose because I have no clue what I would search to find a replacement. It works just fine, I suppose. But something about this search for a vacuum alighted in me a larger problem of postmodern America: the fact that nothing in essence is truly real at all.

This morning I came across the below tweet:

And yes, this is exactly how I feel about it all. I want desperately to be able to find a local store where I can purchase a vacuum, to avoid the Targets, the Wal-Marts, the Amazons of the world, but I no longer even know where to begin. In the city where I live, a place where the downtown was once an incredible haven of small businesses and zero chain stores, ghostly apartment buildings appear now as if overnight, rising up out of the concrete earth, their cheaply painted facades towering over the few businesses who refused to sell their lots. Everything looks exactly the same no matter where you go. Everything has become a simulacrum, a replication, a facade of something behind there so that we do not have to actually face the fact that nothing is there at all. On the internet I am promised happiness in the form of an unbranded vacuum that will likely fall apart within only a few months. In real life I am promised happiness in the form of adding some letters behind my name, letters that go along with a degree that offers me the simulacrum of security, of stability, of having been made in the world. Everything in America is a mold and if I am honest I am starting to also recognize the ways mold functions here dually: I can no longer turn away from the rot that lies at the heart of it all.

Regular readers of this newsletter know that I am currently pursuing my PhD in American Literature/American Studies, with a particular focus on contemporary rural culture and identity. These days I’m especially interested in tracing out the stereotypes attached to the world “folk”. When did it become so heavily associated with rural whiteness and what are the costs of creating this monolith that both idealizes the past and keeps us stuck within these idealized imaginaries? If we dial all the way back, how can we harness the revolutionary powers of folk practice (because yes, of course folk knowledge is also full of resistance, refusal, and survival) and how can that power help us get at some sort of essential truth about America, if there is any truth to be found at all? This is a winding question, but I feel it is one we must answer. We must be willing to look beyond the vapor and see if there is anything that exists here at all.

Baudrillard writes in America (1986) about the spectacle of this place, all of its vanishing points. “I went in search of astral America,” he writes, “not social and cultural America, but the America of the empty, absolute freedom of the freeways, not the deep Americas of mores and mentalities, but the America of desert speed, of motels and mineral surfaces. I looked for it in the speed of the screenplay, in the indifferent reflex of television, in the film of days and nights projected across an empty space, in the marvellously affectless succession of signs, images, faces, and ritual acts on the road; looked for what was nearest to the nuclear and enucleated universe, a universe which is virtually our own, right down to its European cottages” (5).

In essence, Baudrillard is writing about going in search of the points in America where the simulacrum reveals itself; these are the vanishing points, the places where illusion disappears. For him, it’s the desert, the open road, the motel—the famous liminal edges of America. He goes on: “Still, there is a violent contrast here, in this country, between the growing abstractness of a nuclear universe and a primary, visceral, unbounded vitality, springing not from rootedness, but from the lack of roots, a metabolic vitality, in sex and bodies, as well as in work and in buying and selling. Deep down, the US, with its space, its technological refinement, its bluff good conscience, even in those spaces which it opens up for simulation, is the only remaining primitive society… It's primitivism has passed into the hyperbolic, inhuman character of a universe that is beyond us, that far outstrips its own moral, social or ecological rationale… Only Puritans could have invented and developed this ecological and biological morality based on preservation—and therefore on discrimination—which is profoundly racial in nature. Everything becomes an overprotected nature reserve, so protected indeed that there is talk today of denaturalizing Yosemite to give it back to Nature, as happened with the Tasaday in the Philippines. A Puritan obsession with origins in the very place where the ground itself has already gone. An obsession with finding a niche, a contact, precisely at the point where everything unfolds in an astral indifference” (7-8).

I cannot help but think about the emphasis on significance in American culture; everything must be great, or, of course, if it is perceived to no longer be great then we must return it to its former luster, its former allure. As a scholar, I am first and foremost interested in these constructions of greatness, this American mythmaking which is of course not unique to America but which America has generated its own particular breed of. There are stories we tell ourselves to survive and there are stories which survive beyond us, stories whose survival threatens our very ability to exist. This feels to me to be the current state of politics, where a differing opinion can lead to disappearance, where our politicians are etching out a national story that serves only a few and allows only a few to survive within its parameters. I ask to the scholars, writers, artists: what does it mean to live beyond a story? This is not a question of dystopia but one of resistance: to live beyond all odds, to exist even when the story seems set on ending without you.

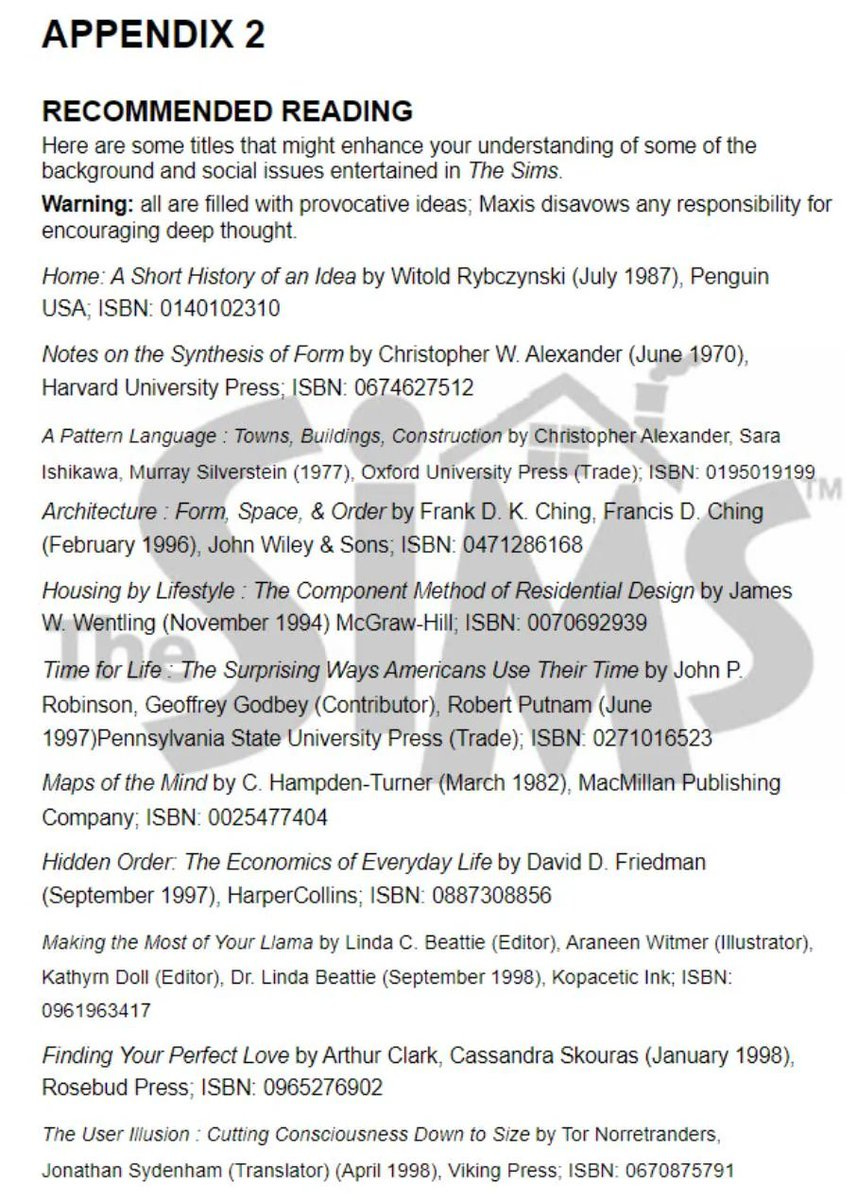

In the first release of the video game The Sims—an excellent exploration of American worldbuilding—gamemakers included a list of recommended reading, full of titles that consider how one will spend time when all needs are met, or at least we are offered the illusion that our needs are met. Consider: this illusion is being broken. We can no longer convince ourselves of safety, of stability, of greatness. Rather than clinging to illusions of an imaginary past, it feels imperative that we learn how to live in this space of breakdown, that we learn what it means to live at the vanishing point. What is over that horizon? We are in a moment where it is up for us to decide.

I leave these tangled thoughts with a passage from June Jordan’s 1975 “Notes of a Barnard Dropout.” I’ve been incredibly disappointed watching my alma mater (Barnard and the larger Columbia entity) bow to demands of the federal government, refuse to protect their students and alumni, and go so far as to rescind degrees of student protestors. I remind myself that it was at Barnard that, like so many other excellent scholars, I was first made aware of my difference as a Southerner; but it was in my years after Barnard, the years before I even held an inclination of returning to the academy, that I learned necessary skills of survival: the importance of community and grounded action in achieving radical change. I come back to Jordan’s words again and again here lately: what is it we are forced to learn, trained to ignore, and bribed into accepting?

In continual pursuit of useful forms of disruption, in the revelatory powers of art and writing, and for the good folks out there interested in building a coalition to together retell the myths of this place —

Spencer

big fan of his work when I got my philosophy degree back in 2009. so much has changed since then, and what we imagined in the realm of simulacrum has shifted and in some ways come true. i wrote my senior thesis on ethnotourism and its relationship to creating an imagine of authenticity to consume.