Hi Folks,

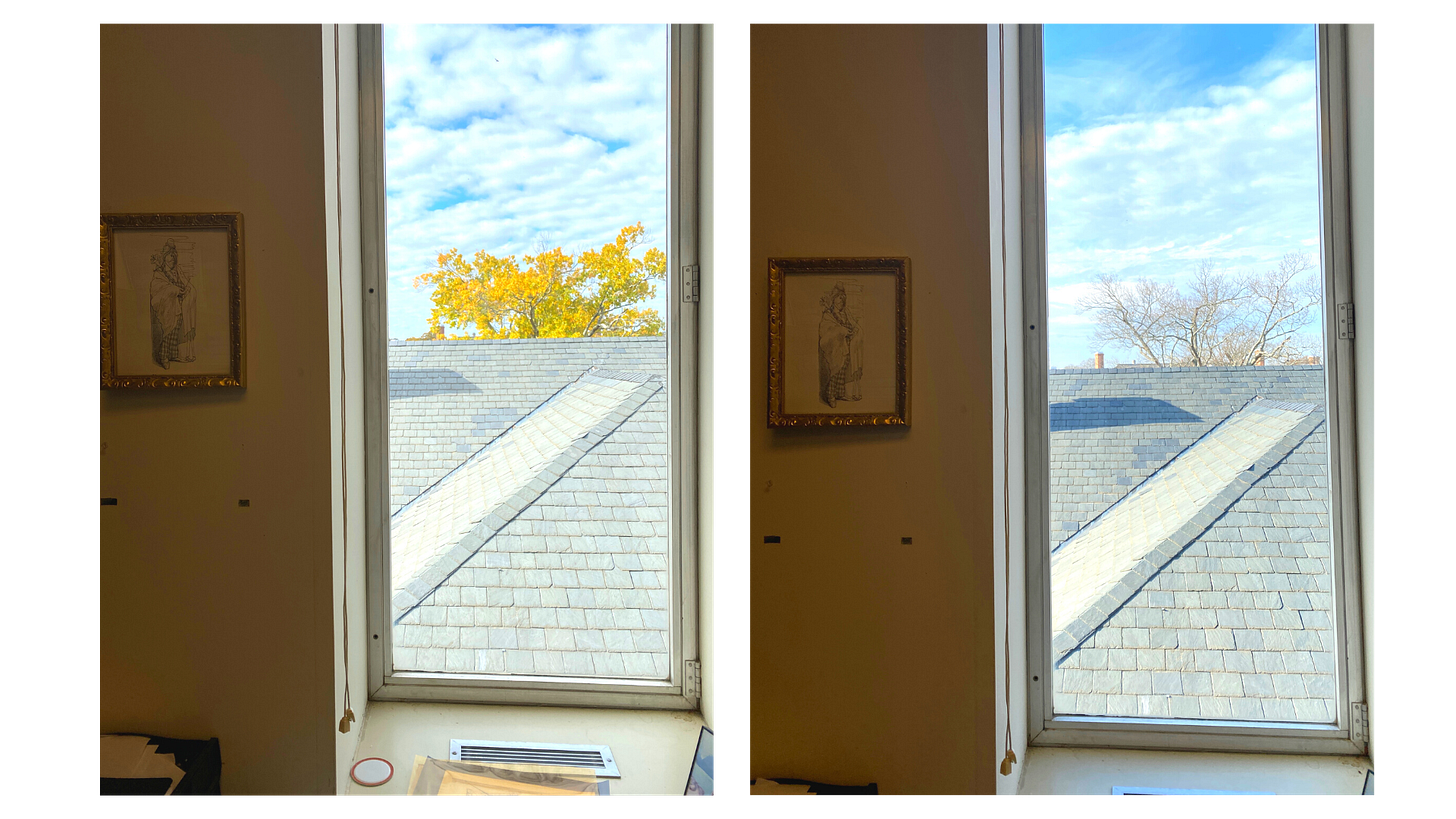

I write this to you sitting in my office on the top floor of the English and American Studies building here at UNC, a place that was once designed as a bunker and now features many small rooms with many small windows that look out at the many beautiful brick buildings of campus. This window faces out to a sloping roof, and behind it, the burst of treetops, their branches jutting up into the air likes spindly hands reaching up to god. Not so long ago, they were cast in shades of yellow, bright against the sky: signs of life and of beauty. Like every year, it seems this change shifted overnight: there one day and gone the next. But of course that is not true. Change is a slow process, one we often fail to notice until the transformation has already been complete.

In a world where things move fast, we often desire for instantaneous change. We want gratification, rapidity, for everything to move quickly. We struggle for patience. We chafe against slowness. It’s not to say that historically we have done any better, but it’s not hard for me to see the ways the internet has both expanded my mind and ruined it at the same time. It feels difficult to read a book. I close out of any webpage that won’t load in under ten seconds. I find it hard to believe that the world can change, or that there is any reason to have hope. I can understand that the place I call home is changing while also feeling it is not changing fast enough.

How, we ask, in 2023, do we still have lawmakers who don’t believe in climate change? Who don’t believe in equal pay across genders? Who fail to respect basic human rights? How, we ask, are there people in the age of internet and television and social media who still believe the same things they believed twenty, thirty, fifty years ago? It sounds easy to ask, but the reality is far more complicated, and I often find myself feeling as if there are two Souths that run parallel to one another. One emerging in metropolitan areas, full of new construction and suburban development and the general consensus that your neighbors at least hold similar beliefs to you. And another one, one that doesn’t try to shy away and yet is hidden all the same: down backroads and hollers, across rolling hills and alongside rivers, in forests and marshes. Places we deem as “rural”, implying a minority, though at least in North Carolina they encompass 78 of our 100 total counties.

Stereotypical constructions of the rural tend to rely on landscape for categorization. It’s far easier to define rural by “not urban” than by its own unique characteristics. Of course, the rural is far from a monolith, and this common generalization is one of the greatest difficulties anyone working in rural studies faces. The rural is vast and sprawling; it is diverse and ever-changing. And yes, it is inherently tied to landscape— which is part of what has always made me question some right-wing politicians who claim to advocate for those in rural spaces and yet continually pass legislation that harms the very landscape that makes these places what they are.

One of the courses I am taking this semester (for anyone new here, I’m a current M.A. student in Folklore at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) focuses on environmental approaches in narrative across Appalachia and the American South, which introduced me to the concept of “slow activism” in rural spaces: the idea that some activist processes— and especially environmental activism— depend on sustained work over time rather than an instantaneous result. As Katherine Borland of Ohio State University writes:

“Slow activism recognizes that processes of natural and cultural recuperation and repair require patience and commitment. It posits that ordinary people can organize themselves into networks to achieve a particular set of goals without giving up important differences—of education, of experience, or of values. And it affirms a plurality of conceptual paradigms under the term environmentalisms.”

Here again I think of the leaves. I think of the trees, which so much of environmental work is about protecting and which took hundreds of years to appear as they are. I think of how astoundingly difficult it can still be to organize people around common interest— and to believe that it is still possible to do so. And I think of the South, which of course I hope to see change, or at least have its hidden histories revealed, and I must remind myself that the work we do as activists here might often feel it is doing nothing at all, but in fact it is part of this larger process of slow activism. It is planting seeds for a different future. It is cultivating communities of care and commitment to oversee their growth. It is not dependent on the individual, nor should it be— none of us will be here forever. I am, in this process, but a leaf on the tree, which cannot sprout without roots and branches and all the other networks of goals required in this slow path to change. Each leaf may look different; each branch, each bud. But there is possibility here to come together for something necessary.

I also believe in the power— and importance— of art in this process. I’ve long been fascinated by The Dark Mountain Project, an ecocriticism movement based primarily in England but rooted across the globe, which believes that in this current moment we cannot stop the collapse of civilization, but that our job as artists and writers and filmmakers and humans is to work to write the stories that both document that collapse and help usher in whatever may come next. It harkens to ancient mythology, to the poets of Greece and Rome, to the stories of collapse that have always permeated. It is, I find, especially pertinent to the idea of a modern South, which is in its own moment of collapse— and which, incidentally, is a region that historically drew heavy inspiration from Greece and Rome, especially in some of these old Southern cities, where plantation culture reigned supreme. “That civilisations fall sooner or later,” The Dark Mountain writes, “is as much a law of history as gravity is a law of physics. What remains after the fall is a wild mixture of cultural debris, confused and angry people whose certainties have betrayed them, and those forces which were always there, deeper than the foundations of the city walls: the desire to survive and the desire for meaning.”

We are now in the wild mixture of cultural debris. We are in the slow collapse, and we require the combination of slow activism with intentional storytelling to see our way out of it. Those who grew up here, its dark histories removed from textbooks and familial conversations, who were blind to the horror embedded in this soil, feel betrayed and confused, a combination that can lead to a dangerous type of anger, one that is uncontrollable and fierce. I understand. I too learned all the myths of this place. I too was angry, full of hatred. All I wanted was to look away— to leave without care, to never again think of the South. That kind of anger doesn’t work. It leads to nothing but abandonment, both for the self and for the soil. And the flip side of that anger is an overwhelming attachment that posits everyone else as the enemy— the kind of anger that got us here in the first place.

But artists, we have always been the ones to tell the stories of the end. If this is a region whose myths are collapsing, we have the opportunity to write new ones in their place. To return to The Dark Mountain:

“If the answers to these questions have been scarce up to now, it is perhaps both because the depth of collective denial is so great, and because the challenge is so very daunting. We are daunted by it, ourselves. But we believe it needs to be risen to. We believe that art must look over the edge, face the world that is coming with a steady eye, and rise to the challenge of ecocide with a challenge of its own: an artistic response to the crumbling of the empires of the mind.”

Here we are, looking out the window, looking over the edge. It is a new year. It is a new season. I will look with the steady eye at the sky, at the branches, and at the stories— new and old. We are already there, at the collapse, at the crumbling. I will not look away.

PROMPT OF THE WEEK

Find a portal through which to stare out through. This could be out of a window, into a screen, at a mirror. Set a timer for five minutes and simply observe. What is different? What is the same? Is this practice of stillness difficult for you? Why or why not?

FIVE THINGS THAT BROUGHT ME JOY THIS WEEK

I’m back on a kick with The Cure. My favorite band of all time for real. A fitting song for this newsletter.

I picked up Mark Prins’ The Latinist this week, and it has fully dragged me in.

After three weeks away, I was reunited with my Nespresso machine. If you know, you know.

Because I am who I am, last week I made the decision to tackle part of the Battery to Beach route in Charleston on foot, and accidentally ended up completing a half marathon. At least the view was nice.

Absolutely loving this Crosby Stills & Nash cover:

@askcarolHappy New Year everyone!!🥳 Wow, what a year it has been. 2022 was an exciting year for us, where we released our debut album and finally got to play live again 😃 And, we know 2023 is gonna be even better! 2022 also had some downers, like the break-in, which is why we are celebrating the start of the new year with this clip from a little over a year ago. It's an amazing song by Neil Young and the rest of CSNY (Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young), in a live looping Backyard Jam version.❤️ Got a lot of great stuff coming up this year, like #SXSW @SXSW, #vinyl, #touring, and soon we'll be up and running with new amps and everything!🎶🎸 And a new mic stand that doesn't slide down, like this one did, is top priority, haha😅 2023, here we come!🤩 Let's make this a great year together, see y'all soon!🥰 #ohio #neilyoung #csny #crosbystillsnashandyoung

@askcarolHappy New Year everyone!!🥳 Wow, what a year it has been. 2022 was an exciting year for us, where we released our debut album and finally got to play live again 😃 And, we know 2023 is gonna be even better! 2022 also had some downers, like the break-in, which is why we are celebrating the start of the new year with this clip from a little over a year ago. It's an amazing song by Neil Young and the rest of CSNY (Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young), in a live looping Backyard Jam version.❤️ Got a lot of great stuff coming up this year, like #SXSW @SXSW, #vinyl, #touring, and soon we'll be up and running with new amps and everything!🎶🎸 And a new mic stand that doesn't slide down, like this one did, is top priority, haha😅 2023, here we come!🤩 Let's make this a great year together, see y'all soon!🥰 #ohio #neilyoung #csny #crosbystillsnashandyoungTiktok failed to load.

Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Had to share this, based on your prompt:

https://www.window-swap.com/

Spencer, I just finished THE LONG HAUL by Myles Horton, which is all about Appalachian activism. I found his idea of a "folk school" to be fascinating. He was definitely one of the slow ones. But so much of what he did worked.