The poem is important, but

not more than the people

whose survival it serves,

one of the necessities, so they may

speak what is true, and have

the patience for beauty: the weighted

grainfield, the shady street,

the well-laid stone and the changing tree

whose branches spread above.

For want of songs and stories

they have dug away the soil,

paved over what is left,

set up their perfunctory walls

in tribute to no god,

for the love of no man or woman,

so that the good that was here

cannot be called back

except by long waiting, by great

sorrows remembered and to come

by invoking the thunderstones

of the world, and the vivid air.

— "In A Motel Parking Lot, Thinking Of Dr. Williams" by Wendell BerryThe poem is no more important than the people whose survival it serves. I have come back to Wendell Berry’s work often this past week, which has felt longer and more exhaustive than any in recent memory. I do not wish to speak here of crisis anymore, wringing my hands and lamenting violence across the board as if my words matter or say anything, as if my renunciation of violence holds any legitimate meaning. This is a nuanced world; we must learn to think deeper than that, to pay closer attention. Our art must as well. In the words of author Hala Alyan, “Make no mistake—handwringing about both sides and whataboutism, equivocation, even silence, isn’t neutrality. It’s taking a stance without the spine to call it that.”

Shortly after my twentieth birthday, I boarded a plane with twenty other students to spend four months traveling to Chile, Nepal, and Jordan to study human rights issues on the ground. I have my own issues with the field of human rights work now—a much longer post—but it was there that I learned to pay careful attention to the world around me. My research focused on critical empathy studies and the role of personal testimony in grassroots and local activist movements, which I had quickly pivoted to focus on after learning of the vast exploitation by Human Rights organizations with a capital HR (such as the UN or Amnesty International), who often capitalized on individual stories and the momentum of local organizations without ever following up, crediting, or compensating the individuals whose stories they borrowed for newsletters, marketing campaigns, and fundraising drives. The same went for journalists; I spoke to individuals who told their story to a reporter only to see it years later in a book in an airport, with no permission given. I learned about governments that have willfully suppressed activists, journalists, and individuals calling out cultural truths and raising awareness of regimes of oppression. I learned about failed Truth and Reconciliation Commissions, who claim to be enacting change when nothing has happened in the course of twenty years. I learned about histories that were hidden from me in my American education, narratives that were written out of the news I watched, the books I read, the conversations I had. I learned in practice what media bias looks like, the way one country can paint another in a wholly different light and the damage this can cause. But most of all, it was that semester, moving week to week and bearing witness to so many stories in so many places, that I learned about the importance of paying close attention.

In Jordan, I sat in a sterile white room with a group of mostly-Americans and a handful of international students, and learned about the history of Palestine for the first time. Nowhere, not once in my education in North and South Carolina, had I ever heard about the rise of Zionism, the creation of Israel, and the brutality that has been enacted upon the Palestinian people, violence much of the world has ignored or looked away from. My host family in Jordan had fled Palestine in search of safety, and it was in conversations with my host mother and the many other individuals who opened their homes to me, that I truly understood that the world can be a heartwrenching place. That all across it, every day, people are forced from their homes—whether through warfare, disaster, climate change—and into new realities. In many ways, crisis is becoming our new state of existence; theorist Fredric Jameson once said that apocalypse is the most defining feature of postmodernity. I don’t want to believe in a violent world—indeed this entire newsletter is founded on the principle that I do truly believe that people are good—but it feels impossible sometimes not to look around and see violence everywhere, in every history book, in every news article, in the tensions that lurk just beneath the surface in America, in the stories that we have told and, most importantly, the stories we have not.

There are so many stories we have not told that reverberate in everything. In every stereotype, in every cultural myth, they are there, painting the world in highly specific ways. I have watched this play out in real time over the course of the last week, as people flocked to social media to condemn violence while also turning a blind eye to the seventy-five year history of violence that has been brought upon the Palestinian people. I do not believe in the language of “both sides” when one side has one of the most extensive military regimes in the world and the other was predicted by the United Nations to be unlivable by 2020. We are witnessing a genocide in real time. And let me make no mistake: I stand here with Palestinian liberation, which is far from what much of Western media has painted it as. To stand for liberation is to believe in freedom against oppression, but it is also to believe in an individual’s right to their own narrative. It is to believe that those with keys to their lands should be allowed to return home. It is to believe that, though history may be violent, the stories we write from here do not have to be.

I want to take a moment to recognize here that many Americans I know have never encountered these conversations before. There are long histories as to why this coverage has not reached us, but if you would like to learn more, I encourage you to take advantage of Haymarket Books’ free, downloadable e-books on Palestinian history and resistance, diversify your media coverage, think critically about the United States’ role in creating stereotypes of the Middle East, and remember that, though we have had images of destruction and rubble pushed down our throats for decades, these places have also been home to thriving civilizations that counter the binaries of Western/Eastern, first-world/third-world, and modern/traditional. Furthermore, if you feel that, as an American, it is not your place to speak on these issues, I’ll note here that as of March of this year the United States has provided $158 billion in military assistance and missile defense funding to Israel, numbers that have only grown in the past few days. Law enforcement officials in Maryland, Florida, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, California, Arizona, Connecticut, New York, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Georgia, Washington, and D.C. have all traveled to Israel for taxpayer funded training trips. America has been entwined in this conflict for years, and we see the ripple effects all across the country: police brutality, racial killings, suppression and opposition. We are not separate from the global violence we see in any way; to condemn only one side is to ignore our complicity in the conditions that have created violence.

If my work in Southern and Appalachian Studies has taught me anything, it is to never accept the first—and often easiest—story that is handed to me. This work has taught me two important lessons: to be willing to look close and to be willing to not look away. Even when it hurts. And it often hurts.

I believe that art can provide a space for that hurt. Art offers a space for conversation, for process, for reckoning. (I highly recommend Marlee Grace’s excellent newsletter this morning on this, above). Likewise, so does the field of cultural studies. As both a folklorist and a writer, my work exists at the intersection of the two. I center my practice around what folklorist Archie Green describes as sitting with the tension, something I have learned well as someone who grew up between the rural and urban and has spent much of the last few years organizing around creative work in rural spaces. It is impossible to be a Southerner—to live in a place haunted by unacknowledged histories of racism, exploitation, and othering—and not feel this tension, which lies just beneath the surface here, ready to burst forth at any moment. But as the region stares down collapse—socially, politically, and environmentally—we must learn to sit with tension if we wish to move forward.

As Green says:

We must touch issues of cultural pluralism at every place they erupt, every place in the polity where there’s a wound, every place where people rub each other on matters of identity, or face, or region, or occupation… Each place of human tension, that’s where a folklorist ought to be. That’s our goal. Public folklore has to move into these areas, and it will only move if young academic folklorists are challenged by these problems… By dealing with issues of cultural pluralism, national identity, rurality, occupational skill, and ethnicity, we may move ahead. If folklorists are not advocates for these issues, then they have little to do. Day to day tasks reduce to rubble… If trained folklorists lack the skill, drive, and creativity to engage in guerilla warfare, then it will be done by other people. And those others may not be conventional types, such as anthropologists, economists, or sociologists. In every other period in American life, when there was a crisis—over slavery, the frontier, or the depression—people arose, whether they were called abolitionists, conservationists, or New Dealers, and responded to the challenge… Will cultural work continue?... Of course, advocates will come to the surface. Whether or not [folklorists] will be part of the process, that’s the big question.

In conversations this past week with other students, learners, and teachers, I’ve found myself returning to a familiar question: what role does the Humanities play in a collapsing world? It’s a central question of my work, and it’s one I think the field of folklore is ripe to study. When I teach my students about what folklore is, I choose to tell them that folklore is a field which asks us to pay close attention. Folklore has both created stereotypes and worked to dismantle them; it is a field which turns on itself again and again and must continue to do so if it wishes to survive. Folklore is about what humans do to prove they exist in the world: the things they make, the things they say, the things they do, the things they believe.

Folklore is a human field; it tells us who we are. But folklore—and art—can also offer us a space to explore who we might become. Creative folklore offers a record: a space for remembrance, a space for healing. A space for liberation and resistance. Artists have never been afraid to sit with that tension, something we must all learn how to do. To sit with that tension in this moment is to let your heart break again and again with the violence that has been enacted, while also to understand that regimes of violence breed violent responses. To understand that the history of the world has been written in blood and that the privileges many of us hold exist as part of that. It is to look beyond and look back, going deeper into the stories presented to us. It is to believe not in a binary but in both/and, to know that two things can be true at once.

I return here to the other half of the Wendell Berry poem I began with. Let the past not be remembered only for the past’s sake. Let the poets speak. Let the people be free.

The poem is important, as the want of it proves. It is the stewardship of its own possibility, the past remembering itself in the presence of the present, the power learned and handed down to see what is present and what is not: the pavement laid down and walked over regardlessly--by exiles, here only because they are passing. Oh, remember the oaks that were here, the leaves, purple and brown, falling, the nuthatches walking headfirst down the trunks, crying "onc! onc!" in the brightness as they are doing now in the cemetery across the street where the past and the dead keep each other. To remember, to hear and remember, is to stop and walk on again to a livelier, surer measure. It is dangerous to remember the past only for its own sake, dangerous to deliver a message you did not get.

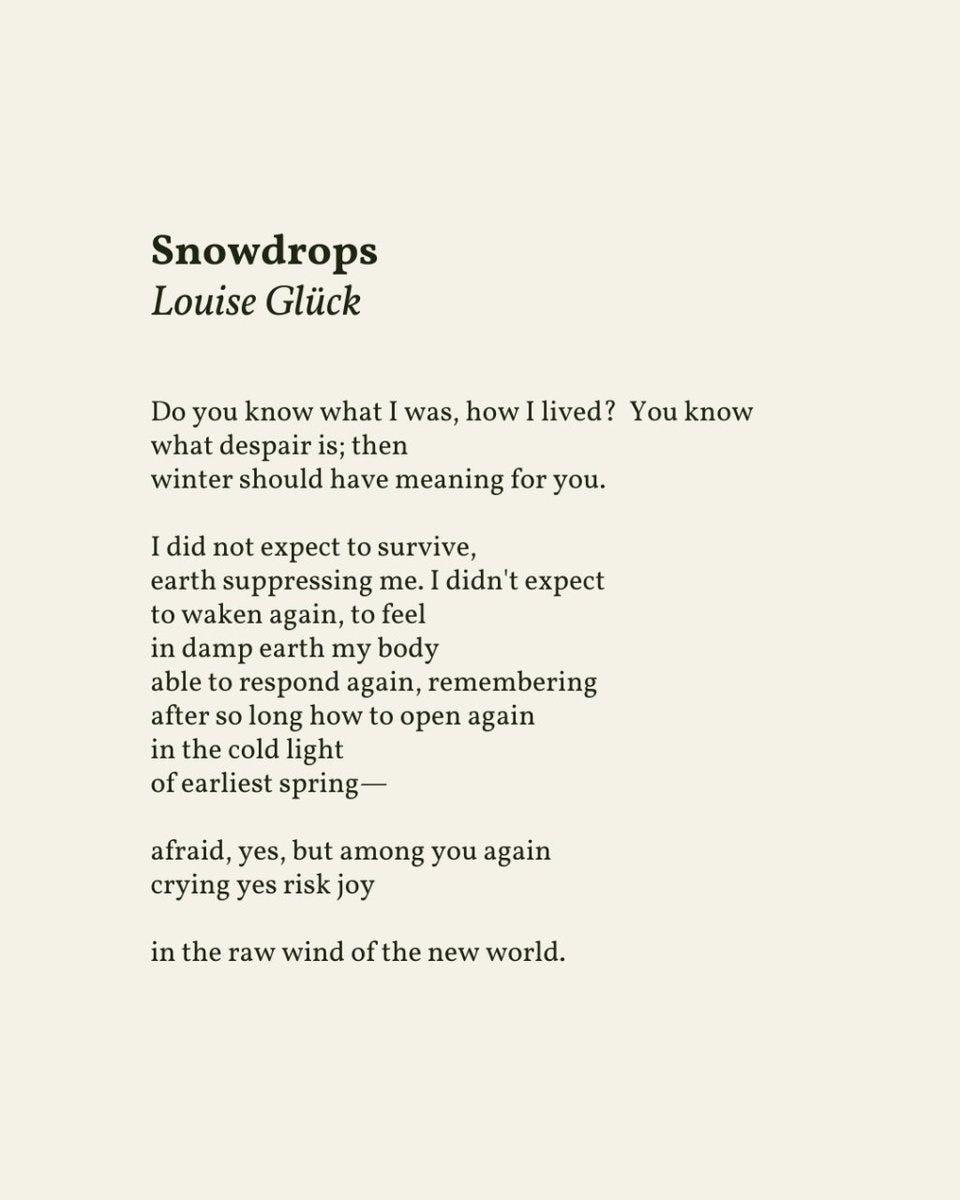

One more poem for the week, as I too am deeply sad about the passing of Louise Glück, one of the first poets whose work I fell in love with. “Witchgrass”, is, I think, one of the best poems ever written, but this one struck a chord with me as of late:

Loved reading this!