Hello Folks,

I’ve spent much of the last year researching apocalypse and climate change in the American South, and much of the last month back home on the coast of South Carolina, a place facing some of the highest climate risk of anywhere in the country. A good portion of this is a combination of thesis fieldwork and novel research; but another—perhaps larger—portion is my own attempt at reckoning with loss. I’ve written before about my own complicated relationship to home, and I’m still trying to answer that same question: what does it mean to love a place you know you will lose?

It was easy when I was a teenager to look away from home; to imagine other worlds in other places, worlds where I saw possibility, creativity, inspiration. Back home, I saw only destruction and pain, both in myself and in the history. Everything held—and still holds—a darker truth. The beauty of place is shadowed by privilege; the landscape is imbued with loss. It was always simpler to turn away in ignorance—to look to other places, or else to turn a blind eye to what was already here. To accept as normal what should be strange, and to make strange what we have accepted as normal. Over the years, these stories become implanted into our lived realities; they become our culture.

In stories of disaster, we often see a world imbued with loss—a shadow of a place that once was. I think of this in every dystopian novel of the last few years: The Hunger Games is meant to reflect rurality (District Twelve, based on Appalachia, is mired in lack) up against The Capitol (a seemingly-glorious vision of urbanity, full of excess), and both, over the course of the books, break down their mythologies to reveal what lies behind. Divergent places us in the ruins of Chicago; The Last of Us in Boston and the American West; Station Eleven in post-apocalyptic Michigan; Gold Fame Citrus in the California desert.

As a genre, dystopia is inherently concerned with disaster, and that disaster is inherently concerned with loss and lack; if we do not feel the risk of what we will lose in these stories, then we feel the distinct lack of what we know today to be true. We see ghosts, both of people and of place.

Most people, when they think of climate change, imagine disaster. We imagine a great tidal wave, a hurricane, a forest fire, an earthquake. We picture the thing we cannot come back from, one singular turning point in time. It will define us, the moment where lack became lived, the moment where all the stories in this genre begin. In our day to day reality, it feels distant and far-off, something concerning only to the worriers, the preppers, those out of touch with reality. The rest of us, we go on. We go on because we must, because life is full of decisions and meetings and bills and responsibilities and obligations and we cannot stop to think about the end of the world because the around us the world continues to go on and on and on and on. Around us, the world seems it will never end nor slow nor cease, and in that space, we are all burned out and exhausted and no one can think about what comes next.

But for the last six months, all I have thought about is what comes next. All I have thought about is the end of the world.

Indeed, I think I have been thinking about the end of the world for a long time. I grew up with the Young Adult dystopia boom, and there’s a piece of me that never particularly left it. Our world has always felt like a dystopia to me, defined by the Oxford Dictionary as “an imagined state or society in which there is great suffering or injustice, typically one that is totalitarian or post-apocalyptic.”

Our world does not have to be post-apocalyptic to be full of suffering and injustice; those exist all around us as it is. We do not have to imagine this. We have only to pay attention, to look at the world around us, and when we do so, we begin to see the cracks.

In 2020, ProPublica ranked Beaufort County, South Carolina, as the top county in all of America set to experience the greatest compounded climate risk. This includes not only a rise in sea level, but also in wet bulb (humidity), fire risk, and heat, backdropped by a loss in agriculture and economic industry. I grew up about an hour from Beaufort, have been reporting on climate change in South Carolina for the last few years, and not once have I heard Beaufort mentioned in any climate conversations I have had. Not once have I seen mainstream environmental movements engage with the county, and in much of the research I have spent the last few months working on, I have yet to find a single person who was aware of the data beforehand—including myself.

When we hear statistics like this, it is easy to lean into despair and disaster. Already this summer has felt full of crisis: wildfire smoke spreading across the Northeast, flooding in Vermont, drastically high temperatures across the Southeast. These are not symptoms of a future disaster, but aspects of the world we live in now. They are not far off; they are not akin to a future apocalypse, but instead acts of Slow Violence, playing out in our everyday realities. It’s the end of the world, or at least the end of the world as we know it.

Last week, I spent an entire day wandering around around a barrier island off the coast of Beaufort County, where saltwater is slowly killing off the slash pines that once dotted the sand. They’re still there, in what is now called a ghost forest, haunted landscapes caused by sea level rise. In the midst of this landscape, I felt so small; what did it mean to be a person when trees could be felled and uprooted? The waves crashed and slid, rising up over my feet. Next to me on the beach, a father and son played in the water, laughing.

It would have felt easy, leaving this landscape, to feel mired in despair. But if this research has taught me anything, it is that there is beauty in this destruction as much as loss. There is regeneration. There is hope.

It is not to say that we will reverse these problems; there is no coming back from this. The landscape responds to the conditions we create. But when I detach from my own humanity, my sense that the world revolves around my own view, my own physicality, then I can see all the other forms of entanglement that emerge. I am not looking at ghosts, but at resistance; not bones, but new ways to survive against all odds. I am detaching myself from the notion that the end of my world is the end of the world. Something will go on, even if I am no longer here to see it.

In her poem, “What It Looks Like to Us and the Words We Use,” Ada Limón paints a new picture of survival:

All these great barns out here in the outskirts, black creosote boards knee-deep in the bluegrass. They look so beautifully abandoned, even in use. You say they look like arks after the sea’s dried up, I say they look like pirate ships, and I think of that walk in the valley where J said, You don’t believe in God? And I said, No. I believe in this connection we all have to nature, to each other, to the universe. And she said, Yeah, God. And how we stood there, low beasts among the white oaks, Spanish moss, and spider webs, obsidian shards stuck in our pockets, woodpecker flurry, and I refused to call it so. So instead, we looked up at the unruly sky, its clouds in simple animal shapes we could name though we knew they were really just clouds— disorderly, and marvelous, and ours.

Even abandoned, there is something beautiful; even in use, there is something of loss. Time is not linear, but interwoven, splicing itself back and forth across the landscape. We are all connected to something—not outside of this environment, but an inherent part of it. And when we begin to think of ourselves that way, something shifts. The climate is not changing, but responding. The question now becomes: are we willing to listen?

In their recent call for submissions on transition and trans-ecologies, the (very brilliant) Mergoat Mag writes:

Transition is not only a movement from one physical state to another, it is also a psychic and societal operation. It is the enfleshment of hope, possibility, and self-determination. What else might the queerness of Appalachia teach us about our hills and heritage? Can we lift the veil of separation hanging between our desire for a new future and the currents of our bleak reality? Can we project another world, another future, into the void left by industrial capitalism — a world characterized by ecological reciprocity. Can we transition? Will we transition?

The old colonial definition of “nature” is wielded like a weapon against trans people. The geography of queer bodies has become the archetype for what many deem “unnatural” — a metaphor we reject outright. So, as we cloak ourselves in grief at the passing of the holocene, as we seek insight from the people wounded by the ill-wrought vocabulary of “nature” that laid the groundwork for colonial violence and domination within the holocene, we seek to build a new vocabulary, one of reciprocity, deference, and care.

When faced with the grim realities of ecological collapse, we defy the sedentary logic of despair, apocalypse, and inaction. We receive the appearance of the void upon history’s horizon not as the apocalyptic impossibility of a future, but as an opening for the creation of futures heretofore unimaginable. There is a challenge at hand, though — how do we deconstruct the colonial image of “nature” as something wholly other than human society? Then, as we move through the grief of losing that once treasured ideal, how do we inaugurate the process of producing new futures?

We, now, are in a moment of transition. It is an ending, certainly. But I am learning in this work that an ending is not total, but circular. Where something ends something else begins. And so we find our ways of coping.

PROMPT OF THE WEEK

What is something that loops in your life? It could be a pattern you find yourself repeating, a physical object (such as a hair tie or clock), or something more abstract. What role does it play? Do you ever break the loop?

FIVE THINGS THIS WEEK

For all my Ethel Cain fans, it’s a Rotting Girl Summer (and yes, I listened to this on repeat the entire time I wrote this).

James Baldwin on optimism: “I can’t be a pessimist because I’m alive. To be a pessimist means you have agreed that human life is an academic matter, so I’m forced to be an optimist. I’m forced to believe that we can survive whatever we must survive.”

These clouds I saw recently, which I cannot stop thinking about:

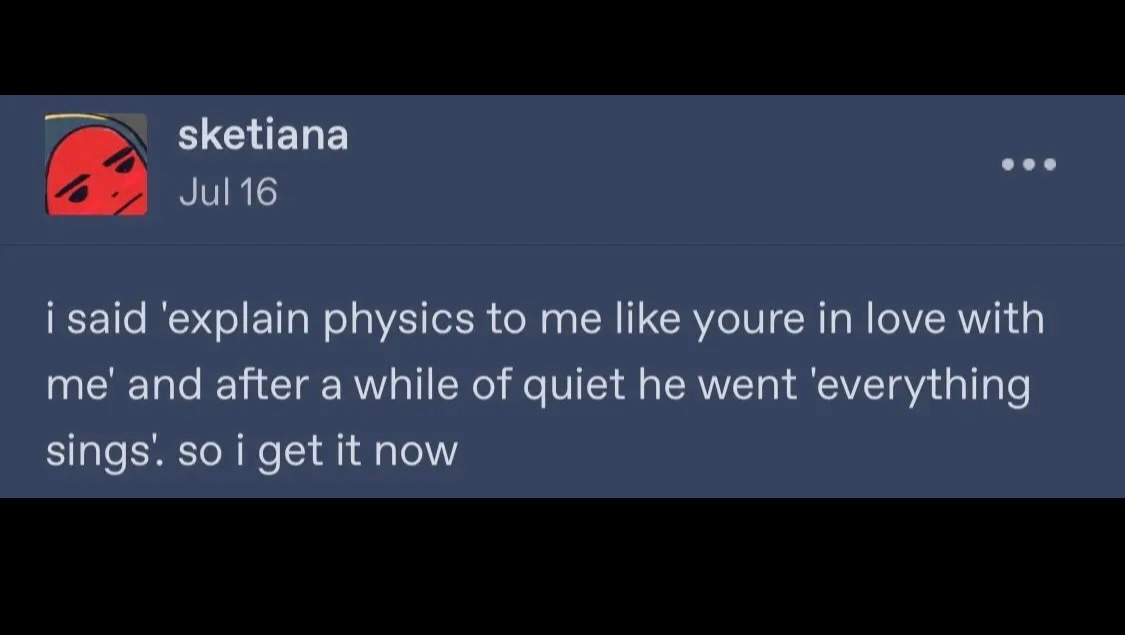

Love is real. Everything sings.

I turned twenty-five a few weeks ago while on the Appalachian Trail, and when we climbed up the highest peak, it was mid-afternoon and we stumbled into a field full of wildflowers and sunlight and there were two rainbows overhead and later that evening I watched the most beautiful sunset I’ve seen in years and a mother and her son showed us their secret hiding spot on the mountain, took a photo of us, and serenaded me with happy birthday and this is how I know that joy is real and people are kind and there is good everywhere in the world if only you are willing to look for it.