Are you from a rural community or the American South? Share your story with us to be published in an upcoming newsletter!

Folks,

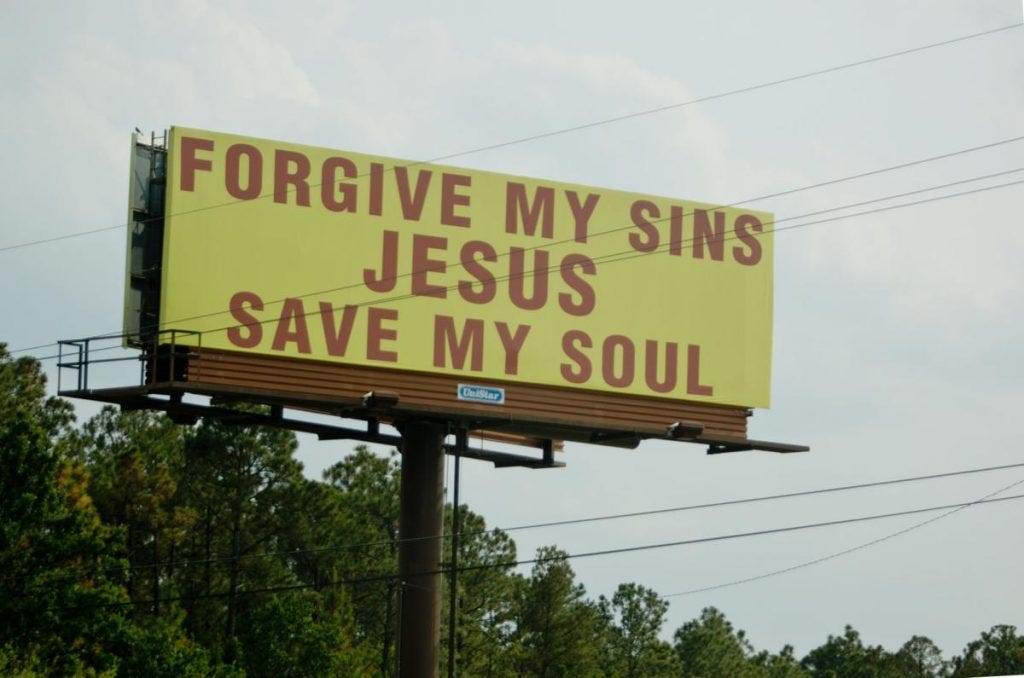

It is midsummer, and warm, the heat stretching out and settling over everything around, dense and coating. I am on the highway again. On my left there are the billboards: go to heaven, go to hell, dial 9 for god, don’t sin. Red letters against neon yellow. This I am used to. Then there is another, up ahead, that catches my eye. Next stop, Italia, it reads, an ad for an Olive Garden. It’s nothing new, or even different, but I find myself struck by it all the same, thinking about this American obsession with the replication of place.

More so than anywhere else I have ever been, this country is obsessed with other places, and with bringing what we imagine to be the experience of them back home, back here. It is striking to me that I can be promised Italy in the middle of the South Carolina backwoods. Of course, it’s tongue-in-cheek— it’s never really going to be Italy— but still, I am fascinated by the marketing scheme of this replication, especially in how largely it is promoted to rural areas. In the last month, I have driven nearly the entire Southeast corridor of I-95 and seen beer ads advertising a mental vacation to a tropical island, the South of the Border signs offering to transport you to what white people imagine as Mexico, Outback Steakhouse taking you to Western Australia, Cracker Barrel billboards that entice you with some sense of home, of grandma’s porch and good ole' southern eats. The list goes on, and it differs and changes all across the country. But when you are up in the middle of the hills, driving down a dirt highway, there’s something unsettling about an ad showing a group of young, tan individuals clustered on a beach and a product that promises to replicate that experience even if you are hours and hours from a beach and no longer young, nor tan, nor carefree. It does not matter where you go in this country; the billboards are there, the promises are hollow.

I would be willing to argue that this phenomenon is not, in fact, the most unsettling in rural areas but in the suburbs, a uniquely American development. Aphorist Mason Cooley once wrote that “The suburbs: signs of life, but no proof.” Drive around any suburb anywhere in America and it will look nearly identical: tan, grey, and white houses clustered next to one another, around cul-de-sacs, horizontal paneling and brick stairways, paved driveways and attached garages. The suburbs sprawl, and they also overtake, neighborhoods popping up wherever there is space available. They replicate themselves wherever they pop up in America, and they seem to pop up everywhere. How strange it has always seemed to me for there to be entire streets of identical houses appearing just off the side of the freeway, their bedroom windows looking out at all the cars passing up and down. All day long you could watch them, each car a whole different person, a whole different life. I am reminded here of a TikTok I saw recently with cars speeding down the highway in opposite directions, white text overlaying the image: you cannot convince me these people are real.

Jean Baudrillard’s simulacrum theory addresses the idea that much of postmodern America exists in a hyperreality. The simulation is “no longer that of a territory or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal… It is no longer a question of imitation, nor duplication, nor even parody. It is a question of substituting the signs of the real for the real.” If this sounds confusing— which it is— I suggest starting by thinking of his most famous example of a simulacrum: Disneyworld.

Simulacrums expose the derealization of the world of everyday reality— that is to say, they demonstrate just how much of our lives is unreal, imagined, provided significance only through our own laws, rules, and interpretations of meaning. I think of it best like this: imagine Disneyworld, with all the lights turned off, all the rides gone silent, still, all the people emptied out. What is left there? Imagine how strange, how surreal, the castles and the cobblestoned streets would feel. The various parks reenacting different environments. Epcot, where you can go around the world in twelve hours. We replicate place so that we can experience everything we wish, but none of it is real. It is a function of capitalism— under which simulacrums thrive— that we must forget the unreality of our manufactured world in order to survive living in it. And by extension, that requires we forgo consciousness. If we are awake and aware, then it becomes impossible to ignore how fixed, how curated all of this is.

This is especially so in suburbia, which increasingly seems to creep in on rural areas, tearing down trees, interspersing neighborhoods with railroad tracks, new development appearing where there was once only dirt, and dust, and endless fields. The idea pushed across America is that suburbia is a type of utopia: enclosed, controllable, sterile and happy. But if it is a utopia it is one that undermines its own premise. Roland Gawlitta explains that suburbias are “real places not only approximating utopian places, but also exposing and de-masking the contradictions behind these real realities and ideals.”

There are two main implications of this for rural communities that I want to discuss here. One, with more and more cities and suburbs falling to replication, with the same restaurants, coffee shops, bars, stores, and franchises popping up across them, rural areas culturally have become a new kind of “last frontier”, one of the few places with character and individuality left. We see this manifest in the continued fantasy of rural life that permeates social media, literature, and film, where we all seem to believe that moving out to the countryside will allow us to escape urban stressers and lay around in the green grass all day drinking tea. In this light, the dream of rural life becomes a type of liminal space where we imagine we will be free to pursue our passions, distanced from capitalism, monotony, and all the drudgery of everyday American life. I can go on and on about this (my college thesis was, in fact, about how even rural communities can’t escape the onslaught of capitalism), but it leads nicely into the second main implication, which is that the push of an industrial— and by extension capitalist— complex onto rural communities facilitates a new kind of hyperreality, one heavily tied to “nostalgia for a pastoral ideal as a way to mask the real problems of an industrial society”, a last-grasp attempt, to quote Marx, to “maintain the old condition things which has been regretfully sacrificed to necessity everywhere else.”

The billboards, the restaurants filling in what they imagine other places to be like, the visions of rural life pushed onto us by popular media— they all substitute signs of something real for what is actually there. They all function in insidious ways, promising us that we will be satisfied with the false experience in place of an actual one. There is no argument here that Olive Garden can in any way compare to a meal in Italy, nor that Outback Steakhouse is an accurate representation of Australia. But the way they are pushed onto communities where international travel and interaction with diverse communities might be far less possible or accepted raises further questions for me. Is it that these companies assume that people in rural communities don’t know enough about the real places to recognize that their product is far off? Is it that they don’t think people care? Am I just overthinking it, and need to get out of my head and just let these massive corporations continue to commodify people, places, and experiences? I am thinking of how many meals my family has eaten at PF Changs over the years, how many times my grandparents have claimed it to be the best Asian food they have ever eaten. I am thinking of the suburban neighborhoods I grew up in, where every cul-de-sac looks the same and every house is simply a painted variation of the other. I am thinking of how I too moved to a rural community because more than anything I was in search of something real, something tangible, a life that I felt like I inhabited each and every day. But the days blur together no matter where I go and the sky shows up grey and clouded each morning and I still have no answers to these questions.

Your prompt this week is to think of the most memorable billboard or advertisement you’ve ever seen. If you have a car, get in it and drive for a half hour. If you’re in a city, walk. Pick something that stands out to you. Take the writing on the ad and use it to begin a story or poem.

As always, thanks for bearing with my ramblings and apologies for how delayed this newsletter is this week. I’ve spent too many hours the past few days driving in the suburbs to block out enough time to write.

See you Friday,

Spencer

This week’s song is Left with a Gun by Skinshape. This is the kind of song I am unable to stop listening to. Since I first heard it on Saturday, it has been the only song I have listened to. I drove for 5 hours straight the other day with this on loop. Every morning I wake up and drink my coffee and look out at the trees and listen to it. I think I will hear these lyrics on loop for the rest of my life: In the end it’s our inception / And life is just perception / For the moment don’t pretend you’ll never be…