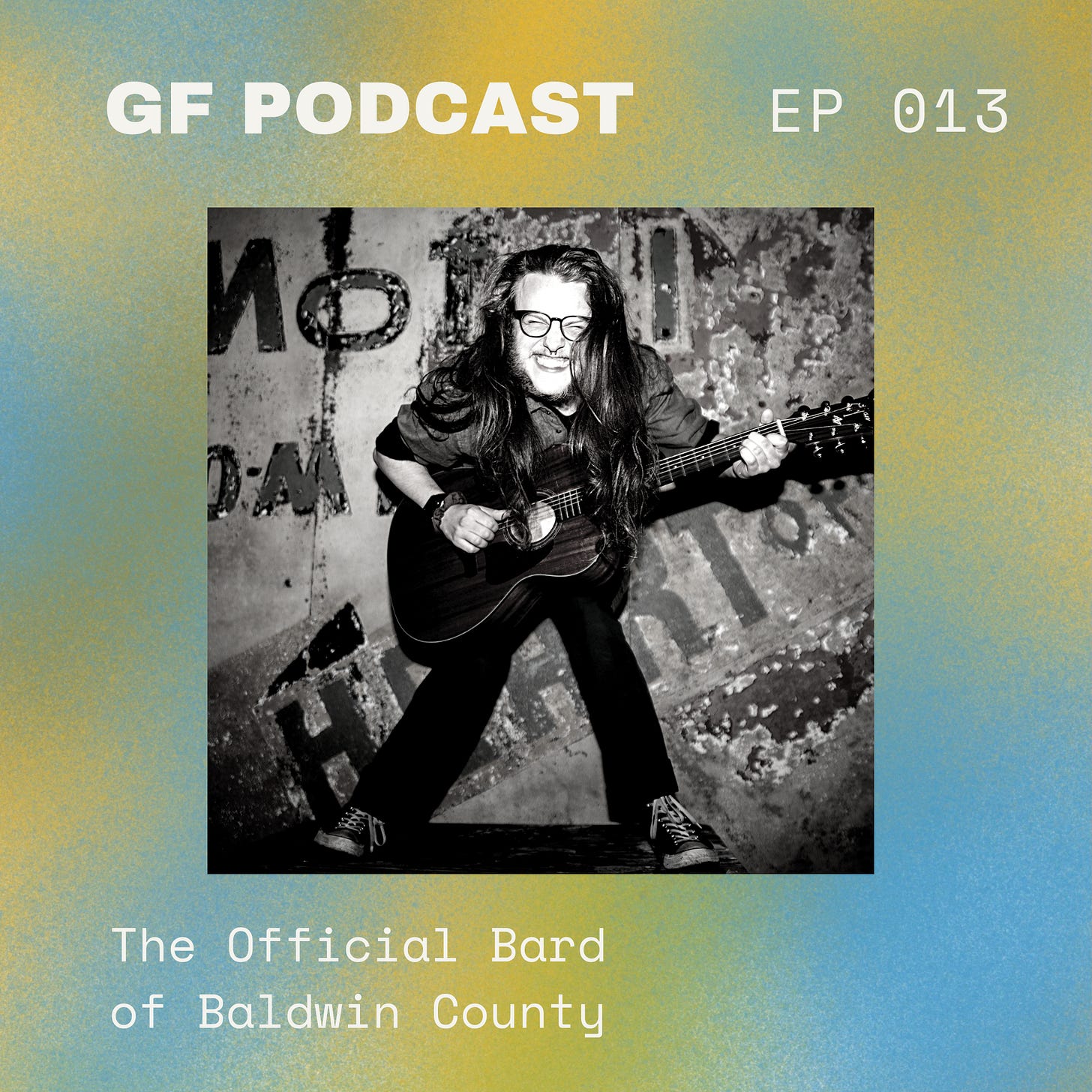

A conversation with the Official Bard of Baldwin County

Transcript from episode thirteen of the Good Folk podcast.

Due to my audio difficulties, the transcript for this episode is available to all subscribers. Full transcripts are generally available to paying subscribers . All subscribers can listen to the podcast here. If you would like to become a paying subscriber, you can do so here.

Spencer George: Hello Folks, my name is Spencer George and you’re listening to the Good Folk podcast. Welcome to 2023, and welcome to season two. Today I’m honored to introduce to you The Official Bard of Baldwin County— an unofficial title, but one the county officials don’t particularly seem to mind, given that their tunes are so catchy.

Jackson Chambers, often referred to as “The Bard”, is an up-and-coming queer folk musician; originally hailing from the Mobile-Tensaw delta, they're currently based out of Auburn, in part due to their anthropology degree requirements.

Raised in the hot morning dew of southern Alabama yard sales and the powdered-sugar dusted walls of their family’s bakery, The Bard makes music to satisfy an eclectic mind. Starting in high-school as the frontman for what was “effectively a shitty Green Day/Misfits cover band”, the Bard is a completely self-taught musician. Despite no formal training, the Bard has wasted no time in exercising their artistic muscles. Fans of lo-fi outsider musicians and folk-punk-revivalists will appreciate their carefully-crafted lyrics and occasional off-key yelps, while the old-time fogeys (and fogeys-at-heart) will enjoy their library of Americana standards.

While a country-goth by trade, the Bard is hard-pressed to stick to a genre for long, incorporating a diverse menagerie of weird instruments and deep-cut tributes. Their high and lonesome tone, alongside their frantic, flamenco-punk guitar playing make them an instant favorite for many new fans. Their newest EP, “the patron saint of something” is available on streaming services everywhere, and they can often be found busking on weekends in downtown Auburn, digging through dusty thrift stores, or on the airwaves of WEGL 91.1 FM, Auburn’s student-run radio station. Overall, they're very glad to make your acquaintance, and hope to see you again soon, ya hear?

There’s no possible way I could follow an introduction like that, so we might as well get into it. Suffice it to say, I’m a big fan of the bard, and I’m a big fan of this conversation. I hope you enjoy.

Bard of Baldwin County: I got distracted by the numbers that popped up on the screen.

Victoria Landers: Spencer! Did you forget to hit record? You had one job!

SG: Thank you. Thank you. I was just going to say, it's been a very long day. I've been teaching since 9:30am. I did one hundred percent forget to click record, so we can really start that from the top.

VL: This is why I usually have the main account, so you don't have to worry about this.

SG: This is why. Yeah. We've swapped the accounts tonight. Okay. I'm so sorry. Let's take it from the top. Why don't we start with— tell me in the very simplest of terms who you are and what you do.

BBC: Cool. My name is Jackson Riley Chambers, and I am the Official Bard of Baldwin County, Alabama. Not Baldwin County, Georgia. I have yet to visit there, even though I probably only live, like, maybe two hours outside of there, but they're the same name. Who knows? I make folk music or folk adjacent music or folk-esque music, and I like to do that. I like to play folk music. That's my spiel.

SG: So I definitely want to get into, in a minute, your whole journey and your career as a musician, but I really want to start actually here with this piece of folk music and what that means to you. As many people who listen to the podcast know, I'm a folklorist. That is my whole thing. And I spend so much time debating what folklore even is with people, and especially folk music, which is what most people understand. When people hear folklore, I feel like they either think of fairy tales and legends and stories, or they think of folk music.

I did an activity with my students recently where I said, what does a folk musician look like, stereotypically? And the general consensus was that it’s a man on a farm with a banjo and a very long beard. And it's not untrue. There are plenty of folk musicians who do look like that, but there are plenty of people who are also doing a lot of really cool things in the world of folklore. And I think your music is such a great example of that. Obviously we're going to get into it and talk about it, but I really want to start there— of being part of this folk tradition or considering yourself someone who makes folk music. What does that word mean to you?

BBC: Now that we're recording officially, I said this a second ago. That's a peek behind the curtain. I'm an anthropology major, and I kind of picked that because right before I came to college, I started learning about Alan Lomax and just like the whole folkways thing, and that really grabbed me. I had always had a big interest in history and stuff like that, and I guess I realized how passionate I was for the fact that humans have been telling each other stories and passing stuff along like this for millennia and millennia and millennia. Being like a steward, I guess, is like the thing that I think is so cool about being a folk musician.

I feel like I kind of have a long way to go in that respect. I've only been performing for, I think, two years now as a solo act, if that. I think it's been two years. But you see all these other people that are in the kind of same sphere and they have this huge repertoire, like Don Fleming's or like Willie Carlisle or any of these other guys, and they have this huge repertoire of stuff. And they've gone and lived with these old fogies who know all these songs and they learned them and they learned how to play the bones and all these other they just have learned all this stuff that kind of is part of the folk musician starter kit.

So I haven't learned that yet. But I do like vernacular music, I guess, and I write about the things that I experience and the things that other people around me experience, or I hope they experience. I hope I don't come off… I hope I at least sound somewhat authentic whenever I write stuff. But I don't know, I try to be a documentarian of feelings and whatnot.

SG: So not only are you a folk musician, you're also just a folklorist. And I'm so glad you bring up Lomax and folkways. And I would love to hear, if you are willing to describe for anyone who's not familiar with that, what is that process? Because there is this whole tradition of folk music and the way in which it's been represented culturally that I think is really important, especially when we talk about moving past some of these stereotypes and doing different things with lyrics. But would you be able to explain that for anyone who doesn't know?

BBC: For sure. And I'm not an expert. This is definitely just stuff that I spend a lot of time googling. I was a TA for my Marine Bio class in high school, and I used to just like, sit there and look at the Smithsonian Folkways website. Basically, back in the thirties, everybody was in the Great Depression, and FDR was like, we need a New Deal. And part of the WPA— I’m 90% sure it's a WPA project. I could be totally wrong. I'm getting a nod. So there we go. Alan Lomax and a bunch of other people went out and recorded all of these different forms of, I'm going to say vernacular music again, because I think that's a good way of putting it. Just like music that people were doing. Folk music, whether that was in prisons, whether that was in churches, whether that was just on the street, whatever. Any time that they were able to find somebody that they could get their gigantic 1930s recording equipment out of their Model T or whatever and then record it. And I just thought that was the coolest thing ever. As a little dorky history nerd who had just gotten out of APUSH, I was like, yo, this is so cool. I want to do this as a job.

And then now there's, like, people like VHS who are doing equivalent to the same thing. Western AF, all those folks. It's expanded outside of just, like, what you'd call folk music. It's not just people on porches playing banjoes anymore. But you're capturing a scene, you're capturing a community, and you're putting it out, and you're archiving it so it doesn't ever get lost. I think that's the part that speaks to me. I'm a big hoarder.

SG: I think that was so well put. And one thing that's always really jumped out to me, both as a folklorist and also just as a storyteller, is the way in which this tradition is really more about telling stories than about anything else. So much of folk music really is about the actual story piece and the narrative coming across. And if you go to any kind of folk festival, you'll often see a lot of people who are just kind of sitting there with their instrument and not worrying about the lyric structure, not worrying about the bridge, the chorus, but really just telling a story over this music. And there are pros and cons to all of this. So much of what Lomax did— and many other early folklorists— was also promote these stereotypes that the South and Appalachia were like, real America and real music, and you had to go into the back roads to find these kind of vernacular forms of folklore that you're talking about. But at the same time, it's a tradition that is rooted in some depth of truth and now is being built on in a lot of ways, which I think you're absolutely contributing to.

BBC: That's very nice to hear. I'm glad that it's like, yeah, I'm sorry. I'm, like, so bad at talking. I never think about it, and then I get to a place where I have to talk and I'm being recorded, and like, oh! Yeah, I don't know. It's a cool thing to be a part of, and I just like… speaking personally in the stuff— because I've started taking my camera to the shows that are happening around Auburn and recording them, and it's just like I personally care a lot about the people that are in my scene. I like them all a lot. There's not a single person that I'm like, oh, man, I don't like that person. And I want there to be some sort of posterity as to what everybody was doing musically in Auburn in the early 2020s. And I just think to be a part of that tradition of recording people and then also getting to perform on the side and be a musician myself, that I'm very lucky to do so.

SG: I've had a lot of conversations with people this week about the element of creating community archives, and I feel like that's exactly what you're describing o, this is your scene, right? This is your community. And I want to get to that in just a second because we've kind of walked around it without actually addressing it, but thinking of going in and creating this kind of body of work of what this community looks like in the early 2020s. It's so weird to say that out loud, like we're in the early 2020s, but we are. And this is such a specific moment of time that who knows down the line what will be done with these things, but there's something about doing that when it's in your own community and really building out this archive that is community rooted, community based. You're telling the stories of people that you know and that you consider part of your own group that is not often seen in folklore and anthropology. And it's something that I think digital technology is really enabling. Now you can just go with your smartphone and everybody has one, and you can just record it and upload it to the internet. And I like to think with this podcast that's so much of what we're doing, too, is creating an archive of what it means to be an artist in the South in the early 2020s.

And I do want to touch on you bring up Auburn, you bring up your scene. So what is Auburn to you? What is this scene?

BBC: It's where I go to school. I'm originally from Baldwin County, Alabama. Also Mobile. Just the general lower Alabama Bay area. Whatever. I came here because I could afford to. They had good in-state tuition and I got some good scholarships. And I kind of never expected to love it here as much as I do. This is not an advertisement for Auburn University.

SG: They should be paying you for this.

BBC: That’s what I’m saying!

SG: We've got to get you on the board.

BBC: They've got enough money. To anyone at Auburn, if you're listening, please pay me. I'm broke. But it just so happened that I found a community of extremely cool people and people that kind of have encouraged me to do music in and of itself. I found the radio station that I work at on campus. If I hadn't found that, I probably wouldn't be talking to you right now, because I wouldn't have been doing music whatsoever. But everybody is so sweet, and everybody is so nice, and it's kind of like, even if I eventually move, it's like, this has been such a good place to get my start, and I've met so many amazing people. [pauses] It's like I start out strong, and then I just can't finish a thought to save my life, but it's a great place.

SG: I think that was a great answer. It kind of leads into my next question, which is, I'm someone who… I feel like I've had so many different homes, and they all impact my life in different ways. Would you consider Auburn a home for you, and what does home mean to you and how does that influence your work?

BBC: I definitely think so. As much as I always love Baldwin County and lower Alabama as a whole, Auburn— I feel like I can be myself more up here than I can at home. Not especially because of, like, my family isn't tolerant or whatever. I mean, that's a part of it, but I think that's kind of it for everybody. You're able to spread your wings a little bit more. But I don't know. It’s comfortable. I can go on bike rides at 2AM around town. It's just very familiar, and it is big and small in a way that feels very comforting. It's like there's a lot of places I haven't explored around here yet, so there's still some mystery to it. But also, I know people that work places and people will smile at you. It's like right in between. Extremely small town where everybody knows who you are and, like, big city where you're just a blip and a speck in the sea, and it's just kind of a good middle ground. Like I said, not an advertisement for Auburn University, because I have problems with Auburn University, as most everybody does with their institutions of education. Auburn as a town is not perfect, but it's very sweet and it's a cool place to live.

SG: I love that you bring up this idea of familiarity, which I feel like implies often that you know a place very well. But I feel like in this sense, more of what you're describing is that this familiarity is that this place allows you to know yourself. And I think that's so hard to find something like that, especially in the South, but when you do, it's really special and it feels really rare. And that enables this kind of community building that often can completely change your life. I don't know if you would agree with that.

BBC: No, I definitely do. In November, I got together with a couple of folks. One primary person, she's now entering the second semester of her sophomore year. And we all got together and organized a whole music festival in town. And just being able to create that kind of community and having all these different artists that we could pull from actually, some were from North Carolina, as a matter of fact.

SG: You'll have to put me in touch.

BBC: Yeah, for sure. The Brothers Gillespie was one of them. I don't know if that name sounds familiar whatsoever. I feel terrible because there is one other one that drove all the way from North Carolina for this festival. It was at like an offroading adventure park that's over by the interstate.

SG: Oh, my gosh, I want to go. Can this be like an annual thing?

BBC: Hopefully. We were actually just talking about it today. We need to get some more people to sponsor it. It's like being able to find myself— obviously there's figuring out my gender expression and figuring out the personal stuff. But also this has been the place where I've figured out how to talk to people and how to meaningfully put myself into new situations that I'm uncomfortable with and figure them out and become a helpful part of a community.

SG: Oh, that's so great to think of being a helpful part of a community because so often community can feel transactional in a lot of ways, of, this is a thing that provides comfort to me and that I'm a part of. But I think that true community and real community is not just about what you get from it, but it's also about what you bring. And this idea of mutual reciprocity which is part of what I love about the arts. You really see that. And it's been amazing just with this project of all the different things of festivals in the works and zine artists who are making things for other things and just people who didn't know each other now connecting and you see how community gets built because people are willing to put themselves out there in this myriad of ways. Which two communities that I feel— both that I identify with— I see this a lot in are both arts communities and the queer community.

BBC: I feel like the experience of following somebody on Instagram because they look cool or like they do something cool, they post like cool art or whatever and then you finally you see like a show or like anything and you're like are you… ? I have a great friend of mine, and the first time I met them, I was like, are you twelve ounce red bull? Because that's their Instagram handle. So it's just the funniest thing. It's the modern are you a friend of Dorothy? But just in terms I don't know. It's so fun. I love it. But then it's like you have a new friend.

SG: In folklore, we talk about transmission and how people— we talk about transmission often of like, information, but there's also with social media a transmission of people, and all these new folk groups being built. Speaking of names, I have to ask. Bard of Baldwin County, where did this originate? Where did it come from? Because it's fantastic. I think it's the best music name I've ever heard. So you have to tell us more.

BBC: Thank you. That's very sweet. I'm very glad. Whenever I was trying to figure out something, I wanted something that was like— I'm assuming you've probably heard of Field Medic before. He does really cool stuff. And I love the fact that his artist name is like a title. It's like an assignment. I always thought that was super cool. Then one year for spring break, my aunt and uncle live out in Arizona, so I went and saw them. And the last day that I was there, we were in Phoenix at the Musical Instrument Museum, which is like the coolest place on the planet. If you ever get a chance to go to the Musical Instrument Museum, please do. Whenever you first walk in, they have this big eye catch gallery of all these different guitars. And it's mainly guitars because that's, like, cool. And one of them was from the State Balladeer of Arizona. I was like, that's like a title you can have? That's cool as hell.

SG: I want that. That's an amazing title.

BBC: It’s like a poet laureate, but cooler. So whenever I was trying to sit down and figure out a name, I toyed with the official wizard of Baldwin County for a while because I had seen like a bit on— it was this old Comedy Central sketch where they had met the official wizard of New York City. And I was like, maybe I'm the official wizard of Baldwin County. But then you slide into Bard and then it sticks. It's alliterative, it's four letters, it goes on shirts. I kind of lucked into it. I'm very happy with it. And as we were talking about earlier, it's just kind of come like what people call me on the norm. And it's very nice. I like it a lot.

SG: It also really seems to speak to the nature of your music, which we're going to delve into the lyrics because we can't not. Your lyrics are incredible, but there are so many stories in what you're doing with your music, and I want to talk a little bit about your journey into music and as a musician and what that's been like before we even get into the lyrics. But you're not just writing songs that are going to sound nice or entertain, you're doing this folklore work and you're also… I mean, a bard is often a poet, right? It's a community storyteller. You're really writing these songs where the lyrics speak the stories of your community in a way that also is kind of fun and entertaining and enjoyable to listen to. And that, in my mind, is exactly what a bard does.

I think it's a very fitting title and I would love to hear about how you got into music and what that's been like.

BBC: It took me forever to get into music. Like, I grew up and I listened to music and stuff. My granddad burned me, like Doobie Brother's CDs. I was actually just talking to one of my professors today. She asked us what our first CD was, and I vividly remember having a burned CD of like, Weird Al Yankovic songs off of LimeWire, which carbondates me as a person because I used LimeWire as a child.

SG: Don't worry, it dates us even more.

BBC: There you go. I love it. I miss it. I miss it so bad. But I didn't get into being a musician until high school where my friends were all in band and I wasn't in band and I wanted to hang out with them more. So I joined band, with very little musical experience and I sucked at it really bad for a couple of months. Then eventually my two best friends now were like, hey, we are in this garage band and we need a singer. You did choir in fifth grade, right? And I was like, yeah, sure, why not? And we did Misfits covers and we did Green Day covers and we were okay. [laughs] We were terrible. It was an experience. It was really fun. But I did that all throughout high school, and we did talent shows and stuff, and we did PTA events. I love looking back on it. It's just like a silly thing I did as a teenager.

But then I got to college, and I met this dude who worked at the radio station on campus, and I got my first solo performance gig as part of that. And then I've been doing it ever since, busking and playing house shows and getting other gigs whenever I can. So that's how I've gotten to this point, at least.

SG: When you think about your future with music, what is your end dream goal? Where would you like to be? Think big.

As long as I can stay connected to music in some capacity for the rest of my life, I'm happy.

BBC: If I'm being very optimistic, I get to tour. Not Beyonce status, but if I could hit, like, working gigging musician, and I get to travel and I get to tour and I don't have to worry about paying my rent and people just like my music, I'm very happy, you know what I mean? Right now, I actually work as a sound guy at the radio station and at the one venue that we have in town. So my plan is now just to kind of get a day job, keep doing music on the side, and then keep working. As long as I can stay connected to music in some capacity for the rest of my life, I'm happy. Whether that's as a musician and performing and getting to tour, that's like, the goal. But even if I'm sticking around here and doing videography or learning how to actually record myself, not on a tape player and doing that for other people, that’s it. If you had asked me ten years ago what I'd be doing with my life, I wouldn't have ever dreamed that I could do music for a career. And I guess I'm not doing music as a career, technically, right now, like on the books, but like, you know, that's the goal, I don't think.

SG: Not yet!

BBC: Not yet, hopefully. Knock on wood.

SG: It's funny when you look back ten years ago. Ten years ago, all I wanted was to write stories and not do it in the South, not even do it in the country, preferably. And I went and did that for a little while and then realized that the ultimate stories I wanted to write were actually about the things I knew and the communities I identified with and that I couldn't do that from far away.

You have Baldwin County in your name, so I'm wondering what Baldwin County as a place means to you in your work and your music and how that has kind of influenced your journey as a musician and as an artist.

BBC: Baldwin County, Alabama, is, I think, the biggest county in Alabama. I don't know exactly by land size, but it goes all the way from the tip of the Gulf of Mexico down to Gulf Shores up into Bay Minette, which is where I lived for all throughout high school. BFE. Love Bay Minette, Alabama. And it sits right across from Mobile, and it's right on the bay and the Delta. And it's hot and it's humid and it's wet, and it is so unpleasant to walk outside in the summer. It feels like you're walking through soup. But despite all that, it's where I grew up, and I don't know why it feels like home, but it does in a way that… I don't know, I feel like everybody has that about their hometown. But I never lived in one town for more than like five years at a time. As a kid, we always moved. We lived over in Mobile for a little while. We lived in Bay Minette, in Daphne, in Spanish Fort. I feel like I got to see all of it, and even the places I didn't live, even the little towns I didn't live in, are just so special to me.

I don't know if it's the fact that my family owned a bakery when I was growing up, and so I would get to go and see all these really pretty venues and stuff. Even just going to people's houses to deliver cakes on a Saturday, and you would just kind of get to see the breadth of everybody that was living there in a way that I don't think you do if you just kind of live in a place and you don't work a job that requires you to go to people's homes on, like, big events and holidays and stuff. I don't know.

It's hard to pin one thing down about it there. Naturally, it's very pretty. There's a lot of biodiversity down there that I didn't really grow to appreciate until I left. It's hard to say other than just it's cool, it's neat.

The hard thing is that when you really live in a place, the way that you're describing it, when you really see it up close and you go to people's homes and you're part of that community, it is everything all at once. It's beautiful and it's horrible and it's somewhere you love, and it's the most hated place you've ever been, and it's home, but it's also not home at all, and there's no easy way to put it into words.

SG: There's never a good way to put it into words. But what I was thinking about as you were speaking is that it's easy to live in a place without really living in a place. I think so many people do that, especially people who moved to the South, and they want to live in, like, Charlotte or Birmingham or Atlanta, but they don't want to live in the South. I know so many people who will say, oh, I live in Asheville, but that's not North Carolina, right.

The hard thing is that when you really live in a place, the way that you're describing it, when you really see it up close and you go to people's homes and you're part of that community, it is everything all at once. It's beautiful and it's horrible and it's somewhere you love, and it's the most hated place you've ever been, and it's home, but it's also not home at all, and there's no easy way to put it into words.

I was thinking to myself this afternoon in one of my classes, I was like, I don't know that I've ever loved and hated something so much at the same time. And at least for me, the only way into kind of processing all of those feelings was to do it through art, but really specifically to do it in this kind of, like, Southern Gothic vein, of, I'm not going to sit here and glorify this place and talk about how wonderful it is, but I do think that there's something really unique and beautiful and strange about it. For me, the only way to process that was to write about it in an equally strange genre.

And I want to delve into a song that I mentioned to you that I cannot stop listening to, which is your song, Cicada Waltz. We're going to link it here. And it feels to me like so Southern Gothic, but also really rooted in this folk tradition. And maybe I need to just put a snippet in so people can listen to it. But I would love to hear how you bring this sense of place into your music, because as you were talking and you were describing Baldwin County and you were like, it's hot and it's humid and it's so sticky, I could just hear the song in my head and I could see the place so clearly. And I've never even been to Alabama.

You do such a great job in your lyrics of bringing these places in and bringing them to life. There's an author who I really love named Claire Vaye Watkins, who writes about the California Mojave Desert. And there was an interview that came out with her a couple of years ago where it was talking about how her work brings these places to life in order to allow them to die at the same time. That's become such a big influence of the way I think about the South— of we have to have art to bring these myths and these traditions and these stories alive and also recognize that there are some that need to die and there are ways in which that can happen. And I just think you're doing that. I would love to hear more about that song and the process because I'm obsessed with it. I can't stop listening to it.

BBC: That is very kind. Thank you so much. I wrote that song, I can't remember exactly the day I had the idea for it, but I've just been fascinated by bugs in the past couple of years. I'm terrified of bugs. Bugs are the thing I'm most scared of ever in the whole world. But my girlfriend is, well, she’s technically not, like, in the entomology program, but like, all of the stuff she's doing is very motivated by bugs. She thinks bugs are really cool. She's also been on a big worm kick recently. Like, she loves worms. But I think I started to really appreciate how cool bugs were because they're just, like, everywhere and they're all so different, like morphologically or whatever.

Then I started doing more research on them and then I was like, oh, I can be really smart and make this little weird metaphor about sleeping for 17 years. Because it's like, as somebody who's been trying to figure out who they are and what they're all about, you kind of feel like you've been in a stupor for a while. And then you come into a new place and you're like, oh, wow. This is who I am, and this is what I want to do with my life.

And I got to thinking about cicadas and how they're so ubiquitous down here in the summertime and how they sound so cool. Then I started doing more research on them and then I was like, oh, I can be really smart and make this little weird metaphor about sleeping for 17 years. Because it's like, as somebody who's been trying to figure out who they are and what they're all about, you kind of feel like you've been in a stupor for a while. And then you come into a new place and you're like, oh, wow. This is who I am, and this is what I want to do with my life. That's in regard to gender or sexuality or literally anything, I feel like there's no stop gap to what you can relate that to.

But I was doing a lot of googling on Wikipedia and reading about cicadas and the different species of them. I think I actually messed up in that song. This is an exclusive, a little lyrical tidbit. The cicadas that live in Alabama, I think actually come out every 14 years and not every 17 years because there's like two different breeds of periodical cicadas. So I just kind of mashed all that together and I wrote a song about it and I hadn't done a song in three four yet, so I was like, I'll do a song, it will be a waltz. Just kind of ended up like that. I wanted to do— Colter Wall has that song, Kate McCannon, and he's got the kick drum on the vet, and I was like, I want to do that. That's cool.

SG: I knew it sounded familiar. I love the song Kate McCannon. That's been like, a huge song for me— I've got a bunch of, like, queer cowgirls, cowboys, all of them in the book I'm working on. And that song has been in the background. I knew there was something really familiar about it. Oh, my gosh, I’m loving this lore. I never would have guessed all of these things. This is why you have to talk to artists about the influence behind their art, because otherwise I would have been like, this is just a really great song. And I would have never thought about cicadas sleeping for 14, 17 years. This is so, so cool.

BBC: Thank you. I'm really glad you liked that one. I think that there is a tendency, because we touched on this already, when you're thinking of a folk musician and you think, dude with a banjo on a farm with a giant beard and overalls. But the thing I've tried to tell myself or stop bugging myself out about is that not every folk song has to be in the key of G and has to have the same song structure and everything. I've tried to write stuff that sounds folky, that is folky. But I've tried to write stuff that is folk music that doesn't sound like normal folk music. Cicada Waltz is one of those that I was always kind of nervous about because I feel like it sounds more modern, a little less timeless than a lot of other stuff that you hear in the folk music genre. And so I'm glad that you like it. I'm glad that it resonates, and I'm glad I get to say to the world that I ripped Colter Wall off here. I feel like that's another important thing about folk music, about any music. It's all stealing. You're stealing from everybody.

SG: Every artist is. Who was it? It was Paul Gaugin who said, good artists copy, great artists steal.

BBC: Exactly.

SG: We're all just stealing from each other. But I totally see the influence— of it's got a little bit of the folk and you also have some blues kind of sounds in there as well. And you can see the Colter Wall. Another person who comes to mind is Adia Victoria who's doing a lot of really cool, like, bluesy folk.

BBC: I haven’t heard that name.

SG: If you don't know her, she's amazing. She has an album that came out last year. Was it last year? It was either last year or the year before. Time is… I have no grasp on time anymore. But it's called A Southern Gothic. So obviously has been really influential in my own work, but she's doing a lot of very cool things as well of saying, this is a tradition that I was raised around, but I was kind of historically excluded from at least in like the world of popular music and like the Nashville scene. And I'm going to reclaim this and make it my own and do it through this kind of Southern Gothic lens. So I definitely think what you're doing has the folk music bend, but you're making it your own, which is really what every great artist should be doing.

BBC: I appreciate that. That's very sweet.

SG: I want to talk about your most popular song, which is Heavens to… Is it Heavens to Murgatroyd?

BBC: Heavens to Murgatroyd.

SG: Murgatroyd. So before I even get into the lyrics, what is Murgatroyd?

BBC: I had to Google it. I took the title from old Hannah Barbera cartoons. Is it Choo Choo? Oh, I feel terrible. I can't remember his actual name. He's a pink cat, but he was a character in Hannah Barbera cartoons. And I watched a bunch of Boomerang as a kid and he would just go, Heavens to Murgatroyd, exit stage left, even! That was his thing. But it was like Murgatroyd, from what I understand, from my Googling and from my research that I've done, is like just an old last name, which is whack. And I think we need to bring it back. Me, personally, if I met somebody named Murgatroyd on the street, I would flip because that's a cool ass name. You sound like a transformer.

But he's a little bit fruity and the song is a little bit fruity. So I was like, why not? It sounds cool. It's like sometimes I will see something, I'll think of a title or I'll see just like a string of words and I'm like, that's cool. I want to make that my thing. I want to claim that for me. So then that's a song title. I've got like, Phoebe Bridgers of Madison County in my notes app right now. It's just dumb stuff.

VL: The cat's name is Snagglepuss. Just FYI.

BBC: Snagglepuss. Thank you. Thank you. I was going to be so mad at myself if I didn't think about it. You are literally my savior.

SG: It's really cool what you do with that of taking something that is familiar from your childhood and then you're kind of picking up on these other aspects of it and then making it your own with the song. And obviously the song deals with a lot of elements of queerness and I just love these lyrics that say, I wish I could pick and choose my parts / trade a singing saw for my possum heart / I want to be what I want to be / but I guess despite all of that, despite everything / I'm still me.

This is just like top notch lyricism, but you're also kind of addressing your own identity through this and all these different things you want to be and the way you express that in the world and how you deal with queerness. And it's so cool to see that in folk music and to see that again in these traditions that have historically just not made space for this. Can you just tell us more about the journey of that song? I don't know, have you gotten to perform any songs off this album yet?

BBC: I have. A lot of time, I feel like I'm a way better live artist than I am recorded. I feel like I kind of suck on recording.

SG: Well, I'll definitely have to see you live then. I think you're great on recording.

BBC: Thank you. That genuinely means a ton. It's like I get such bad— this is a mini tangent, and then I'll return to the actual question you asked me— but I have a ton of anxiety about recording. I wish I had gotten into all of this stuff in high school when I had all the time in the world to sit and make all of the really shitty stuff you have to do as an artist to be kind of good at something. I'm sure that you all relate to that just in terms of everything, whether it's writing or literally any other artistic stuff. You just have to make so much shit before you can start to make good stuff.

SG: Oh my God, and then you're going to spend the next, like, ten years ashamed of it. I'm afraid to look at the notes on my phone. I have notebooks locked in a back drawer. Sometimes I think of stuff that I used to perform at open mic nights, and I'm like, who let me do that? [laughs] But then also you can recognize in your artistic journey, I wouldn't be doing what I am today— and I'm sure I'll look back in five years and be like, who, let me say that on the Internet? But yes, I'm so glad you bring that up because it's so true and people don't talk about it enough.

BBC: Yeah, exactly. There's so much of it. But long story short, I lean into recording on tape and recording on stuff like that because it's crunchy, and if it sounds bad, I can just blame it on cassette tape and I like how it sounds anyway. But hat whole song, I can't remember how I wrote it, but I think one day I was just feeling down and it was one of those times where you go and you stare at the mirror and you're like, is this my face? Is this who I am right now?

And it's like all the dysphoria or whatever and stuff just started coming out and it probably went through a bunch of iterations. I could probably look through my old phone recordings and find like 15 different versions of it where I was trying different stuff out. But I feel like once I was able to get a couple of verses in— and there's like a line about Judith Butler and a line about Wendy Carlos and all of these. I say Judith Butler. I have read about Judith Butler and I think we might have read one of her articles or essays or something in my anthropological theory class, but reading theory is so hard for me, my little peanut brain can't do it. And so it's like, I know of ideas. I know gender is a performance or whatever. So there you go. That's a cool little metaphor I can throw in there. And so it just kind of all came together. Then I was able to put in a weird little slow country section at the end of it and then sweep it back up. Again, I was like, that sounds cool. I hope people like it. And people have, and it makes me really happy.

SG: I was going to ask about audience reception and performing it live. In a lot of the conversations that I have with different musicians, the songs that really always seem to resonate, especially in the world of folk music, are often songs that deal with queerness and identity because there has been just such a dearth of those for so long. So you say people really resonate with it. What has that been like? And have you gotten a chance to perform this live and actually see people's reactions to it?

BBC: People yell the lyrics and it makes me want to cry literally every single time. The best time. I helped set up this little show on Halloween that was basically just the people that work in student media at Auburn. We were just trying to get a little get together. It was very last minute, but it was me and there's an excellent indie rock emo band called Radio Decay that are like Auburn DIY royalty. They've just been in the scene for so long and they're the best. But it ended up just being like basically all my friends that were here and watching this show and people were just screaming the lyrics and it genuinely made me tear up.

As a creative, you do stuff for yourself, but then having that be shouted back at you quite literally and have other people relate to it as much as they do is just the coolest thing in the world.

I think being able to have people recite sing along with you to something that you wrote and then it also be something that's very personal and about your identity— I feel like as a musician, you write stuff for yourself a lot of the time. As a creative, you do stuff for yourself, but then having that be shouted back at you quite literally and have other people relate to it as much as they do is just the coolest thing in the world. Especially when it's in person too. It's like, oh my gosh, you're literally yelling at me. I can smell your breath and you need to brush your teeth. But thank you. I don't know, it's just the coolest thing ever.

SG: It's times like this that I wish I was a musician instead of a writer because writing, it's the same kind of principle, but it does often feel lonely. But I have similar experiences of people who will just email me and truly it means so much and I save all of them. I think art forces you to hold up a mirror to who you are in a way that is really jarring and really painful. And the honest truth is that you probably will not make good art or what feels good to you until you go through that process. But it is not easy and it will almost take you out, but it is kind of necessary and there's that kind of light at the end of the tunnel. If you go through that process and you really start making the art that feels true to who you are, there is the beautiful part when people see themselves in it. That is in my mind how community is built and what it is and what it means and why art is so important and so powerful. It's not just about bringing beauty to the world. It's really about saying this is the deepest truth of who I am, and other people saying I am there, too.

I think art forces you to hold up a mirror to who you are in a way that is really jarring and really painful. And the honest truth is that you probably will not make good art or what feels good to you until you go through that process… If you go through that process and you really start making the art that feels true to who you are, there is the beautiful part when people see themselves in it. That is in my mind how community is built and what it is and what it means and why art is so important and so powerful. It's not just about bringing beauty to the world. It's really about saying this is the deepest truth of who I am, and other people saying I am there, too.

BBC: For sure. For sure. It's weird and I feel like a lot of the time, I don't know, I feel like I'm definitely neurodivergent in some way. I've never been able to get diagnosed or whatever, but I feel like I've always kind of been on the outside of things and being able to write stuff and then have people, like you said,they're in there too. It's just so cool. It's such a unique thingm, and I feel so lucky to be a part of. Even with, like, The Circle, which is— shout out Ren, shout out to our mutual friend that put us in touch— they run The Circle, which is the arts magazine on campus. Every every semester they do Snaps, which is this big open mic. If you submit stuff and it gets in you can go and do a reading for it. Just to be in a space where everybody is on an even keel and everybody wants to see what you've made and wants to hear your story or whatever is so cool.

The fact that I get to be a part of that and actively create and just support other people that do it… This is not good for an audio medium, but at the venue I work at, there is the Opelica Auburn Film Art Collective and it's these two old dudes who show weird art house movies and stuff. And one of my really good friends made a mini zine for their next little season of all the movies that they're doing. And it's so cool. It's like I get to be in a community where people are making stuff for other people's projects and I don't know, it's so cool.

SG: No, it really is just incredible. It's amazing to see how the way you describe it feels so supportive and so just mutually reciprocative, where people want to pass down the support that they have been given. Something that comes up in a lot of these conversations is that we all can kind of agree that we really want community, especially as artists. But that doesn't make it any easier to find it. I know when I was in college, I felt like I was applying left and right to join literary clubs or be on the board of this or that and just getting rejected left and right. And it's so easy to feel like you're never going to find it. You're never going to have that community.

As I've gotten older, I think I just realized you can build it, right? You don't have to wait for these people to open the door for you. You could say, hey, I really love your music. Here's a zine that I'm going to make, use it or not. But now we have some sort of connection. It is so hard to do that. So much of what I feel like I've learned as an artist the last few years is like, just tell people you think they're cool. Just message people on social media. Have no shame about it, because most artists are really cool and really welcoming and we want to help each other in some kind of way. Everybody can feel intimidated and these scenes can often feel closed.

I found this even like, working in Southern journalism, there are a couple of big name publications and it's hard to break into and you can be so certain that something is a community for you and still not be sure of your place in it. But I think that the way you're talking about this is— sometimes you just have to show up and you just have to let people know that you like what they do and see where it goes.

And maybe that's not the community for you. You never know where life is going to lead you, but sometimes it's just about taking the opportunity to let someone know.

BBC: Yeah, that's exactly the thing that I've learned most in all of this stuff. I just try to be radically happy and radically enthusiastic about everything that my friends are making and everything that I think is cool. And there's like a line in Beatific Vision and Self-Derision in Evil B Flat, which is my proudest work of being an obnoxious musician who writes really long song titles. But it's like I love this world and the people prone to loving. I love love. And I love being able to be enthusiastic about stuff and, like, have you know, it sounds so cornball and so cheesy. And I hope that I don't come off way too much in this and also in real life. I try to rein it in, but I just want people to know that they're really appreciated, and especially if you're making art and you're being extremely vulnerable. Coming from somebody who is extremely shy and extremely averse to having eyes on them anytime other than being on stage, I know how hard it is, and I know it kind of sucks in a way, getting up on there. Especially if it's a crowd that's not into you and it's not digging you, it sucks.

But trying and doing the damn thing. I mean, there are scenes that I've been trying to get myself into. I feel like there's a bit of an old guard. I feel like it's in any scene, but, like, the people who have been in music for a little while and you kind of have to prove yourself that you're not like, a flashing pan or you don't suck. That's a thing that I've been trying to work on. The people that own the big venues and the people that you know are in with the people that know the big people.

There's always going to be another group that you have to fight your way into and be like, hey, listen, I'm making stuff and you're going to listen to it if you're so pleased, I'm not going to force you, but I would appreciate it if you listen to my music. I'm going to be really nice to you until you do, and then we're going to be friends. We're going to be best friends. But I don't know, just being able to be a part of something is so cool. And like I said earlier, you mentioned, like, it's a mutual reciprocity thing.

I never go into anything wanting something. I always genuinely want to just let everybody know that they're appreciated and we could never talk again. But I'm still going to tell you your set was great. If you're doing something cool, I want you to know. That's how you build communities.

And then you get to do other cool stuff for them going forward. I get to go and record my friend's band playing or whatever and I think I've kind of diverged rapidly from whatever the original question was. But it's so cool and I love being able to tell people that they're doing good because I know how awesome it is when somebody tells me the same thing, and especially if it's like a musician to musician thing or a writer to writer thing or an artist to artist thing in general. I don’t know. it's so cool.

I never go into anything wanting something. I always genuinely want to just let everybody know that they're appreciated and we could never talk again. But I'm still going to tell you your set was great. If you're doing something cool, I want you to know. That's how you build communities.

VL: I was gonna jump in and say that every artist has a praise kink, because everyone just loves hearing that they did good. Because you get so nervous creating this thing you're really proud of and then you're done with it and you're like, okay, I did the thing. Did you hate it? Do I need to kill myself or do I need to create more? Everyone has a little imposter syndrome, I think. So just going up, being like, I really love this, I really truly enjoy it. That's how I've met a lot of my artist friends. I think it's so important of really uplifting the community that you're in and just saying I really like what you did, good job, do it again. I want to hear more.

SG: What I was going to say, as well, one of my favorite things you do is you actually speak to the audience in your music. And the first time I listened through to your album, I wasn't expecting it. It made me smile so much, where you let the audience know, like, I'm grateful for you and I love you and thank you for listening. I just feel like more artists should do that because it's so wonderful and I've never seen it done before.

BBC: I've always had really bad self esteem problems. If I'm just being completely honest, I hate myself a lot of the time. It's not even to be a bummer, just keeping it a buck. And so it always means the world to me that people interact with my stuff in any meaningful way. Because there's so many people that make fantastic art and then they post it online and it gets very little interaction. You get five likes, you get thirty likes or whatever and that's all. There's a whole other conversation to be had about how much you care about interaction on social media.

But the fact that people take the time out of their day to listen to my music that I recorded in my grandpa's basement, like that means the world to me. That is literally the coolest thing ever that I get to sit here, and I recorded my first EP in that closet over there. Ignore how messy it is. And then I recorded the second one and this one that I'm releasing next Friday in my grandma's basement. So the fact that people have actively sought it out in some cases and also shout out to Kelsey Herzog from the Yellow Button for literally changing my life because she was the person that put me out into the world and showed people that my music exists. I could cry, literally. People who do independent playlist, curation and stuff like that are the modern day Alan Lomaxes, I guess. Somewhat, maybe.

But I don't know. It means the world to me. And if I can make people smile by saying, hey, I love you, it's like, thank you for listening, that's the least I can do. I should be paying you to listen to my music, hell.

SG: The moral of the story is that sometimes these little forms of interaction on both sides, you never know how much they mean to people. You have no idea what your lyrics mean to someone who really needed to hear that song and know that this is possible for them too, right? And vice versa. So the moral of the story, I think, is just tell people you like their art and their work and who they are.

I just love this conversation so much. You're such a light and joy and presence and I need to come to Auburn because I've never been to Alabama and it sounds very fun. And, yeah, shout out to Ren for putting us in touch. Ren is the best. And unfortunately, we are coming up to our hour time and we do always end the podcast with… we ask everybody the same final question and you can take a minute to think about it, you can interpret it however you would like, but the question is, what do you believe in?

BBC: Oh, hell, you can't drop that on me at the end of a podcast. That's like, what you ask on somebody's deathbed.

SG: Sometimes I give people warning and sometimes I like to just go full chaos and drop it and see where we go.

BBC: What are your values? What comes after death? Come on, now.

SG: We've had a variety of answers. We've had everything from cryptids to art to myself to my work. So take it as you will.

BBC: I like to believe that people are inherently good. People are inherently good. I will say that. And even if they suck really bad on the outset… No, there are some people that do suck. Maybe I take that back. Maybe everybody isn't inherently good. Maybe some people just do suck. No, that's too cynical. People are inherently good and if you're nice to people, people can change and making stuff that is nice and putting that out into the world is extremely necessary and I think that it helps a lot. There are some people that suck and you might have to be addicted to them a little bit but then hopefully maybe they come around.

Also, I believe in cryptids. Maybe some of them, maybe not mothman but we've got to have a skunk ape somewhere. Maybe. There's got to be a gorilla that got out of the zoo and we just haven't found them yet. I don't know. I'm not a cryptozoologist.. The cryptozoology concept EP— that's down the road. That's coming out one of these days. I've got material.

SG: It’ll be a collaboration with the folklorist and the musician. We'll team up.

BBC: That's what I'm saying. I literally almost— before University of Western Kentucky shut down their folklore program, that's where I was going to go to grad school for public folklore.

SG: You can always come to Chapel Hill. We are a small but mighty group. I will say we're very fun. I might be a little biased but…

BBC: I think I'm actually following UNC Chapel Hill, like whatever Instagram account they have. But yeah, I think that you should be nice to people and try to make people laugh and you should go decorate your house in stuff that's ugly and weird and look for the small things and eat salt. We only live like 80 years. Don't worry about what you're eating. Have fun. I don't know. I love you.

SG: We love you. This is such a great variety of answers. Our regular listeners know this, but around here at Good Folk, our whole thing is that we just really believe that people are good and that good folks are everywhere. And that you have to believe that. This is where our title came from. I really just believe that people are good, and especially in the South and in rural places. We’re good folks. They're out there. Everyone is a good folk. And we love all of you and we love you. And for anyone who wants to follow your work and your music and where you go from here, how can they find you? How can they get in touch?

BBC: You can find me on Instagram @OfficialBardofBaldwinCounty. You can look me up on Bandcamp, Spotify, Apple iTunes, Apple Music, Microsoft, Zoom. Facebook. I have a Facebook page. I don't really ever use it. I need to do that. I'm still kind of in the figuring my shit out phase of being a DIY musician. But Bandcamp, Instagram, Spotify. I'm streaming everywhere. I also have a website, officialbard.carrd.co, which I need to update, but that's where I live on the Internet. I'd give my address, but that wouldn't be smart.

Message me, reach out to me, talk to me. I love you. And hell, I had another thing I was going to say. Oh, new EP coming out next Friday the 28th. It was a thing that I wrote in a day, so it kind of sucks, but it's about birds. I wrote it all in a day and recorded it the next day. It's weird and it's rough and it's funky. It's not funky. One song is funky, but it's about birds. So that's what's next for me.

SG: Get on it, people. Follow everything. And I'm so excited for the new album. Thank you so much for being here. To everyone listening, wherever you are, have a good day, good night, good afternoon. We love you. We'll see you soon.

Love this!